The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recently made welcome changes to the guidelines known as “Clinical Knowledge Summary” used by GPs and other primary care practitioners for diagnosing cauda equina syndrome. The revised guidelines should lead to earlier diagnosis of this severe condition.

Within our own cases, we have seen the difficulties that can arise when the wrong decision is made as to whether a patient should be referred on for specialist treatment. The clearer protocol will aim to ensure that patients are quickly progressed to treatment for the best possible recovery.

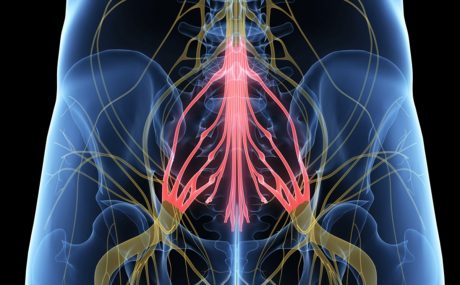

What is cauda equina syndrome?

Cauda equina syndrome is a narrowing of the spinal canal that causes compression on the nerves at the bottom of the spine. Cauda equina syndrome (so named in Latin because of its resemblance to a “horse’s tail”) is most often caused by a prolapsed disc, but anything that causes compression, such as an injury to the bone, a tumour, or an abscess may lead to cauda equina syndrome (CES).

The compression can cause weakness and numbness in the legs and feet, and deterioration in bladder and bowel control. It is a medical emergency, and if not diagnosed and surgically treated within hours rather than days, can lead to permanent paralysis with loss of bladder, bowel and sexual function, significantly affecting the person’s quality of life. The earlier the pressure on the cauda equina can be alleviated by surgery, the better the expected recovery for the patient.

Diagnosis is based on the identification of signs and symptoms known as “red flags” because these symptoms should alert a clinician to the possibility of cauda equina. The previous NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries set a high bar for urgent investigation, which often meant that patients’ symptoms did not meet the criteria for an urgent MRI scan (the investigation of choice), or that by the time their symptoms did meet the criteria, it was too late and they were left with permanent disability. A full list of the updated “red flag” symptoms are set out at the end of this article.

New symptoms have been added to NICE’s summary, including “bilateral sciatica” which usually presents in the form of pain and numbness down the back of both legs. In our experience of bringing clinical negligence cases arising from a delay in diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome, one of the most common features is bilateral sciatica not being taken seriously by GPs.

Another key change in the guidelines relates to the classic warning sign of altered bladder function. The previous guidelines required urinary retention or urinary incontinence. The revised guidelines have a lower threshold and include “difficulty initiating micturition [urinating] or impaired urinary flow”.

This is particularly important in the context of symptoms which can creep up slowly and by which patients can feel embarrassed. Sometimes patients will not notice that there is some change in sensation or even that their bladder or bowel habits have changed. Many are also in pain, may have been taking codeine or other painkillers which can cause constipation, or have some pre-existing incontinence problems, all of which can complicate the patient’s description of their problems. GPs will need to take a careful history of these symptoms to ensure that they have the full picture on which to base their treatment decisions.

Altered bladder function is one of the key tell-tale signs of impending cauda equina syndrome. Again, the early warning signs that precede incontinence are often dismissed. The medical research demonstrates that by the time the patient has become incontinent, unless surgery to decompress the cauda equina occurs very rapidly, the patient is often left incontinent, requiring catheterisation for the rest of their life. By recognising difficulty in beginning to pass urine, and a change in sensation, patients could be diagnosed in the potentially short window where there may be some changes to bladder and bowel function, but where voluntary control of the bladder is maintained.

It is recognised in the medical literature that patients who have advanced to being in urinary retention are likely to have worse outcomes than those where surgery occurs whilst some voluntary bladder control remains. However, in our experience clinicians often wait until the patient has reached urinary retention before treating the situation as an emergency, which is often too late. The new guidelines emphasise the importance of difficulty urinating (not simply being in urinary retention) and so this should lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment, and better outcomes for patients.

Fortunately, cases of CES are rare. However, the implications can be catastrophic. The effect on stability and mobility can leave patients reliant on various mobility aids and unable to participate in everyday activities with their friends and family, or even to properly care for themselves. The need to develop bladder and bowel regimes involving catheterisation, suppositories and with the possibility of accidents is hugely limiting. The effect of the person’s quality of life can be devastating.

This review of the NICE guidelines is welcome news all round. Patients are now more likely to be referred earlier where these concerning signs and symptoms arise. GPs will have greater certainty, and secondary care facilities will receive patients at an early stage, making for better outcomes.

The cases of SG and RL

Stewarts regularly act for patients who have had late diagnosis or delayed treatment of CES. In many cases, clients are the ‘walking wounded’ who find that because their symptoms are not obvious friends and family find it hard understand the true extent of their injuries.

One recent case involved a lady injured in her late 30s. Although a diagnosis was made in A&E, doctors decided not to act until after the point where she had lost lower limb function. Although she made some recovery after surgery, she struggled to care for her young children and to continue to work. Her difficulty walking meant that she had to avoid distances of more than a few meters and could not walk safely on uneven ground. SG suffers incurable pain and severely disturbed sleep. To account for her and her children’s current care needs and her likely care needs in her 50s and 60s the defendant agreed an award in excess of £3m.

Stewarts’ Leeds team recently won a similar case for RL, where a community physiotherapist failed to pick up on the warning signs and symptoms of an impending emergency. This case demonstrates that it is not just doctors who need to be aware of the changing guidelines.

Updates to “red flag” symptoms

The updated NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries on cauda equina red flags are as follows (the new sections are in bold):

- Bilateral sciatica

- Severe or progressive bilateral neurological deficit of the legs, such as major motor weakness with knee extension, ankle eversion, or foot dorsiflexion

- Difficulty initiating micturition or impaired sensation of urinary flow, if untreated this may lead to irreversible urinary retention with overflow urinary incontinence

- Loss of sensation of rectal fullness, if untreated this may lead to irreversible faecal incontinence

- Perianal, perineal or genital sensory loss (saddle anaesthesia or paraesthesia)

- Laxity of the anal sphincter.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Clinical Negligence pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Media contact: Lydia Buckingham, Senior Marketing Executive, +44 (0) 20 7822 8134, lbuckingham@stewartslaw.com