Pensions are complicated beasts that can be complex to share on the breakdown of a marriage. There are many different considerations to take into account, including the value of the pension, the basis on which it is to be shared (ie capital or income) and the age of the parties, not to mention tax and lifetime allowance protections.

Ellie Hampson-Jones and Katriona King review a case that addresses these issues and the circumstances in which a pension sharing order can be varied.

The judgment of His Honour Judge Hess in T v T sheds some light on the process where the value of a pension changes between a pension sharing order being made (before the decree absolute has been pronounced) and being implemented. The judgment also reminds practitioners of guidance provided in the PAG Report of July 2019.

The usual process

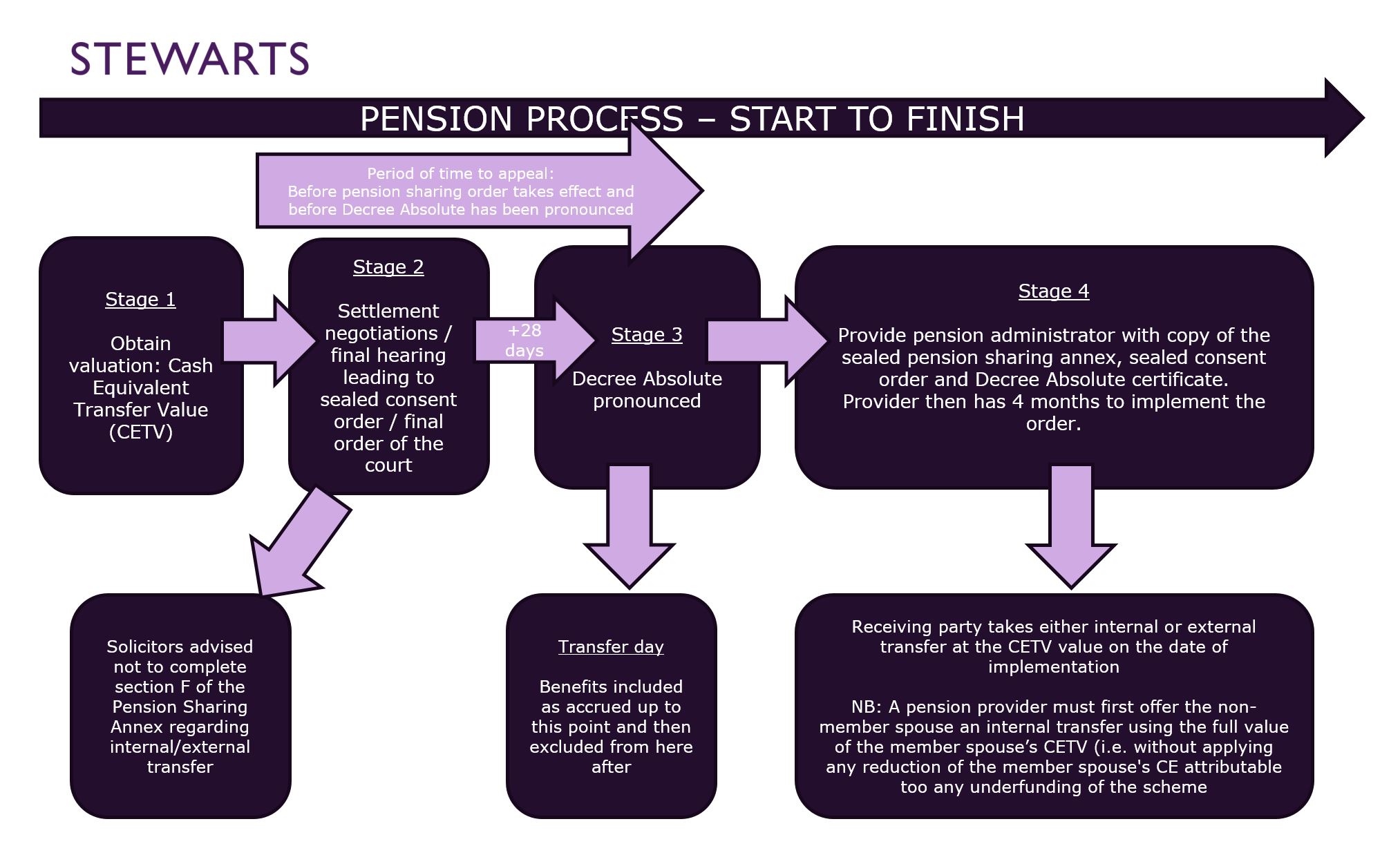

A diagram summarising the end-to-end process is set below:

As can be seen from the above diagram, a difference in value can (and usually does) arise between the valuation first obtained and the value of the pension when a pension sharing order is implemented. This is what is often described as “moving target syndrome”.

To counter the effect of moving target syndrome, practitioners follow the guidance set down by Mrs Justice Baron in the case of H v H [2010], namely that a pension sharing order should be “specified only in percentage terms”. His Honour Judge Hess reiterated this in his judgment, making clear that a pension-sharing annex should not include any formula for producing a certain level of income or for a particular monetary sum to be transferred. The logic follows that if the figure is expressed in percentage terms, both parties share proportionately in any increase or decrease in the value.

What happened in this case?

Mr and Mrs T separated in 2013, and financial remedy proceedings commenced in 2014. Contested proceedings continued until a final hearing in the autumn of 2015. At that final hearing, the respective pension situations of the parties were found to be as follows:

- Mr T had a pension with Company X, the cash equivalent (CE) value of which was £826,125

- Mr T also had an Aegon pension with a CE of £76,990

- Mrs T had a Legal & General pension fund with a CE of £77,232

The final order provided Mrs T with a 40% pension sharing order in respect of Mr T’s pension with Company X. This percentage was arrived at by adopting a broad-brush approach rather than a detailed mathematical calculation. There have been no suggestions that either the overall order or the 40% figure was wrong.

For several reasons, including arguments over detailed drafting points, the finalised order was a long time coming and was not sealed until May 2016, seven months after the final hearing. In that time, neither party had applied for the decree absolute, meaning that stage 3 of the pension process diagram above was not reached.

In late 2016, three developments in relation to the Company X pension occurred:

- When the pension administrators received the pension sharing annex (the Form P1 that allows an individual to share in a member spouse’s pension), they responded requiring Mrs T to select an external transfer as the pension scheme did not permit internal transfers.

- Mr T’s pension fund was re-valued in October 2016, and the CE amended to £1,795,362. A further re-evaluation in June 2017 gave a CE of just over £1,650,000. Thus, the CE value of the fund had increased significantly since the original judgment in 2015.

- In December 2016, Company X introduced a new policy whereby due to underfunding, it would reduce the CE of pension funds for external transfers. The valuation in June 2017 provided a CE value of £722,138 for the purposes of an external transfer.

Mrs T’s application

Mrs T, relying on the information that the pension scheme would not permit internal transfers for a non-member spouse, became concerned that the 40% pension sharing order would provide her with considerably less than was envisaged at the time of judgment. She applied for a declaration that the 40% share should apply to the full CE value of £1,795,362 as it had to the £826,125 in 2015. It is worth noting that the court would not, and indeed could not, have granted such a declaration. Meanwhile, Mr T applied for a variation of the pension sharing order on the basis that the 40% share should be varied downwards to a percentage of the full CE value designed to provide the same cash lump sum as envisaged in 2015.

It appears no one in the legal teams was aware that where a pensions provider is offering only a reduced CE value on external transfers, it must offer the receiving spouse an internal transfer, notwithstanding any general policy permitting only external transfers. Therefore, a non-member spouse receiving a share of a pension cannot be forced to accept a lower value pension share.

Mr T’s variation application

Variations of pension sharing orders are extremely rare; indeed, as His Honour Judge Hess observed, there appear to be no such reported cases to date. The statutory requirements, under section 31(7) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, are:

“… the court shall have regard to all the circumstances of the case… the circumstances of the case shall include any change in any of the matters to which the court was required to have regard when making the order to which the application relates.”

Mr Justice Mostyn recently suggested that only a “recalibration of the payment schedule” can be approved by a court applying section 31 of the 1973 Act and that the original order “is not variable as to overall quantum”. The only way to succeed in varying the amount would be to meet the extremely high Barder criteria. As explained in our previous article, a Barder event is regarded as an exceptional one in which criteria must be met.

Nonetheless, even the less stringent test as adopted by Mr Justice Bodey in Westbury v Sampson [2002] 1 FLR 166 requires circumstance to have changed “very significantly, and/or for cogent reasons rendering it quite unjust or impracticable to hold the payer to the overall quantum of the order originally made.” His Honour Judge Hess, applying this test, determined that the only real change in circumstances, the increase in CE value of the pension, failed to establish the necessary ”very significant” change for three main reasons:

- Mr T’s legal team seemed to be operating under a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of CE values in relation to a defined benefit pension;

- No hardship would be suffered by Mr T as a result of Mrs T receiving a 40% pension share. Mr T’s own benefit from the increased pension value increased even more than Mrs T’s would; and

- It was predominantly Mr T who had delayed the pronouncement of the decree absolute and therefore prevented the early effecting of the pension sharing order. As such, he had left himself open to the possibility of a greater impact of the moving target syndrome.

Conclusion

Accordingly, the variation application was dismissed, and the parties directed to implement the pension sharing order on the original basis of a 40% share to Mrs T.

Lessons learned

There are three main points to take away from this case:

- Where a pension provider is offering only a reduced CE value on an external transfer, that provider must offer an internal transfer to the receiving spouse.

- Pension sharing orders must be expressed as a percentage share in the final order to accommodate moving target syndrome and allow any changes to CE value to be absorbed by or to benefit both parties equally.

- The report produced by the Pension Advisory Group in 2019 should be essential reading. Although appearing only in Appendix V, the report directs that “Family Lawyers would be well advised in the meantime not to tick either boxes in section F”.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Divorce and Family pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.