At London International Disputes Week, lawyers from Stewarts and Penningtons Manches Cooper took the stage to spotlight fresh trends shaping dispute resolution between India and the UK.

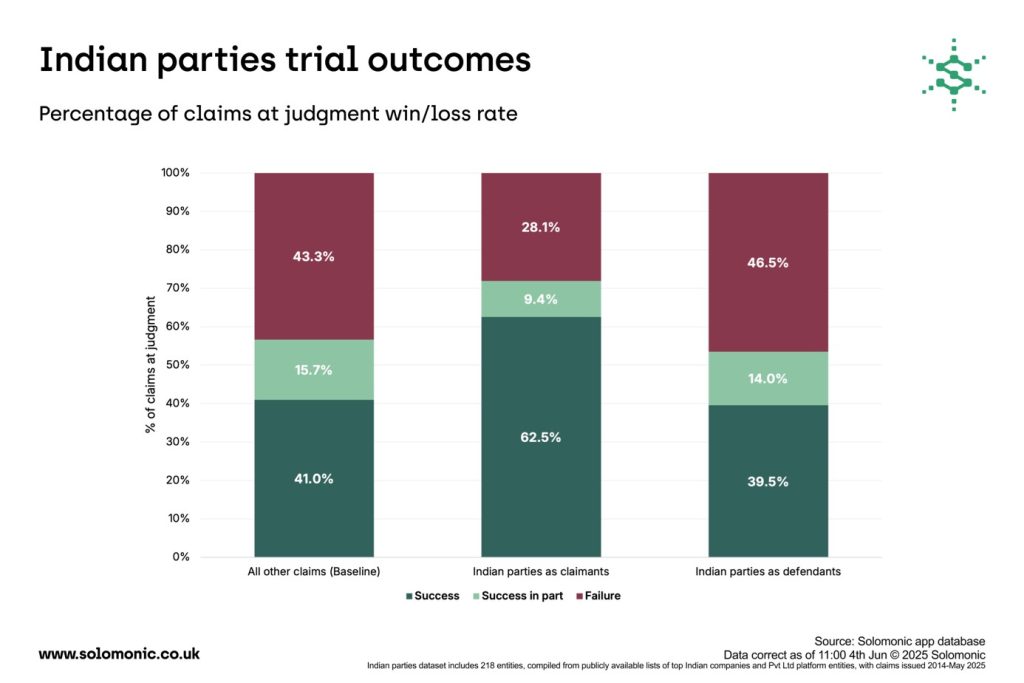

Backed by Solomonic’s data analytics team, the discussion revealed a number of growing trends among Indian parties, with the most significant finding being that Indian claimants had a significantly higher success rate (62.5%) compared to all other claimants (42.3%), highlighting the growing confidence in the UK judicial system among Indian litigants and the increasing strategic value of cross-border claims.

Unlocking access and opening gateways

English law offers multiple gateways for Indian claimants to bring cases before English courts, which are especially useful when the defendant is based overseas. Some of the most integral gateways for Indian claimants contemplating a claim are:

- when the defendant is domiciled in England;

- when one defendant is domiciled in England and is treated as an ‘anchor’ allowing other ‘necessary or proper parties’ to be joined to the claim against the anchor defendant;

- when the claim relates to a contract with an English jurisdiction clause, the contract is made in the jurisdiction or subject to English law, or the breach of contract takes place in England;

- (in tort claims) when the harmful event occurs in England.

English courts are also decisive when it comes to deciding jurisdiction, which is crucial in cases involving allegations of fraud across borders. In Re Harrington and Charles Trading Co Ltd (in Liquidation) [2023] EWHC 307 [Ch], the court rejected a jurisdiction challenge in a billion-dollar fraud case involving two Indian companies and a consortium of Indian banks.

The defendants argued that India was the ‘centre of gravity’ of the dispute and was the more appropriate forum. However, the English court held firm, and ruled that although India was a possible venue, it was not ‘clearly more appropriate’ than England. The ruling relied on key factors such as proper service on the defendants, the claimant’s residence in England, and the location of substantial documentary evidence being in England.

Speedier solutions

Indian litigants are attracted to English courts due to their reputation for swift rulings and a proactive approach to summary judgment. The streamlined procedures and decisive posture of English judges offer a compelling route to resolution, which is crucial for litigants. Indian parties in contractual claims have a median claim length of one and year five months. For claims that end with summary judgment, the length is even lower at less than a year (357 days) – an attractive prospect from the English courts compared to Indian courts, which are well known for their backlogs and delays.

Typical disputes

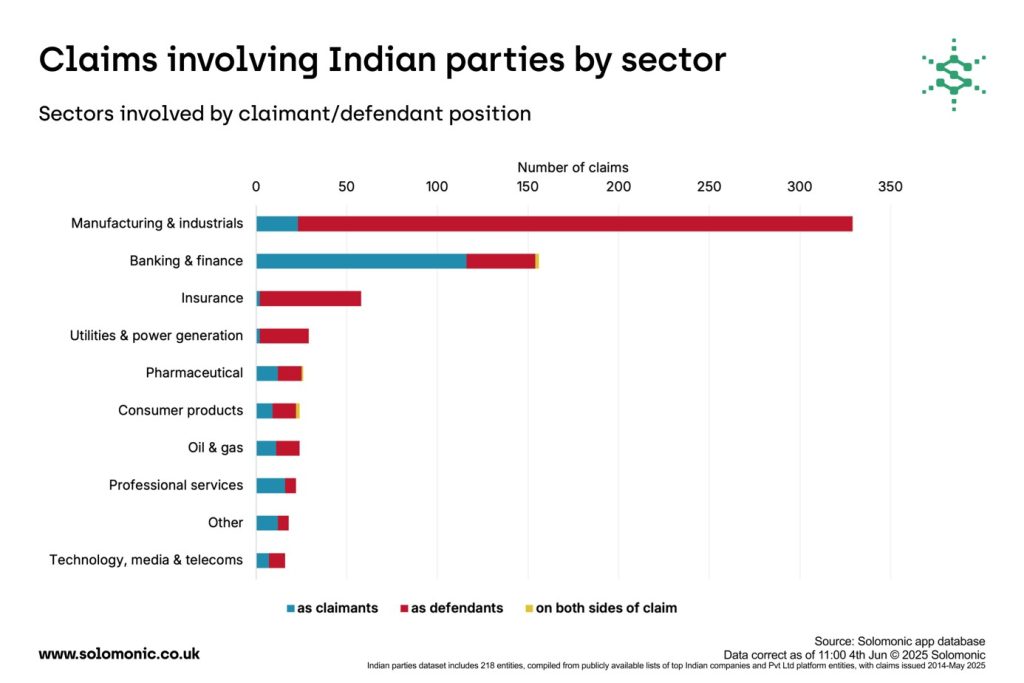

Indian parties most frequently appear in disputes within the manufacturing and industrials sector. These cases typically centre around breaches of contract, breaches of statutory duty, and negligence – reflecting the commercial complexities involved with cross-border industrial dealing.

In the banking and finance space, Indian parties heavily feature as claimants, often bringing high-value claims with a median value of £13.88 million. These disputes commonly involve non-payment under guarantees, with defendants frequently arguing that such guarantees are invalid due to alleged breaches of Indian law.

For example, in IDBI Bank Ltd v Axcel Sunshine Ltd & Anor [2025] EWHC 442 (Comm), IDBI Bank secured recovery of a $143 million loan from Axcel Sunshine, an Indian surety. Axcel Sunshine argued that a Letter of Comfort underlying the loan was provided only for optics, contravened an Indian legal requirement to obtain permission from the Reserve Bank of India, and was not meant to be relied upon. The court dismissed the claim and concluded that Letter of Comfort had created a binding guarantee that was enforceable in India.

This judgment reflects a growing trend that English courts are increasingly trusted to resolve complex, high-value disputes involving Indian parties by delivering predictability, credibility, and global enforceability.

Ease of enforcement

The reciprocal enforcement regime operating under the Foreign Judgments (Reciprocal Enforcement) Act 1933 and The Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments (India) Order 1958 allows judgments in both jurisdictions to be enforced in the other.

Earlier this year, the State Bank of India and other lenders successfully enforced an English bankruptcy order against prominent businessman and former Indian MP Vijay Mallya in connection to the collapse of the Kingfisher Airlines, securing recognition of a debt exceeding £1 billion. In State Bank of India & Ors v Mallya [2025] EWHC 858 (Ch), the Court of Appeal upheld the order, dismissing Mallya’s appeal and affirming the enforceability of the Indian court judgment.

A look to the future

The recently concluded India-UK free trade agreement promises to unlock new trade opportunities for both countries across goods, services and investment. However, with increased commercial activity comes the associated increase in legal friction. Indian parties litigating across all different sectors will see increased prominence within English courts with the growing likelihood of contractual breaches and cross-border enforcement challenges. The enforcement of Indian judgments in England will also likely become a regular feature of the legal landscape as commercial ties deepen between the two countries. English courts will be expected to grapple with recognition and enforcement issues arising from Indian court rulings.

These emerging trends demonstrate that English courts are not only willing but fully capable of serving as an efficient and effective forum for Indian parties. Their openness to cross-border litigation, efficiency, and pragmatic approach to enforcement makes them a strategic choice for resolving complex disputes.

This article has been co-authored by Sherina Petit, partner, Head of International Arbitration and head of the India Practice, and paralegal Nick Ong at Stewarts, alongside Phillip D’Costa, partner and co-head of the India Group, and Harriet Campbell, senior knowledge lawyer at Penningtons Manches Cooper.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Commercial Litigation and International Arbitration pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.