Defamation claims, including those brought by Hollywood actor Johnny Depp and Brexiteer businessman Arron Banks, have been under the spotlight recently. These claims have been mentioned alongside an increasingly polarised debate about strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs). Emily Cox explains what SLAPPs are and considers recent examples and future implications of SLAPP claims.

You may have seen references to ‘SLAPPs’ and ‘anti-SLAPP laws’ recently and wondered what they are. A SLAPP describes an abuse of the legal process designed to intimidate an opponent, typically by way of a defamation or privacy claim to prevent publication of an unflattering article or footage.

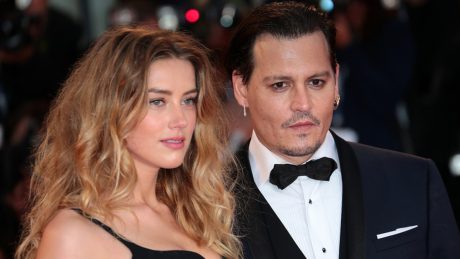

In the US: Johnny Depp

In the US, anti-SLAPP laws exist in many states, given this abuse of the legal process is seen as a threat to the First Amendment right to free speech. States such as California have strict anti-SLAPP laws, while others offer weaker protections (until recently, Virginia, for example).

In Johnny Depp’s defamation claim against Amber Heard regarding her Washington Post op-ed, Mr Depp is widely thought to have filed his case in Virginia because of its then more lenient anti-SLAPP laws. Ms Heard later sought to deploy the beefed-up anti-SLAPP laws to argue before the jury that she had written on a matter of public concern regarding domestic violence and so should be protected from a defamation claim.

In England and Wales

There is no SLAPP-specific legislation in England and Wales, though our defamation laws include a public interest defence. In addition, our privacy laws involve a routine balancing of privacy rights under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) against the public interest in the right to freedom of expression under Article 10. The present government appears to view the pendulum as having swung too far in favour of privacy rights and, among other initiatives, issued a call for evidence earlier this year on the challenges presented by SLAPP litigation and possible reforms. The consultation closed in May and, on 20 July 2022, the government published its response – more on this below.

(i) Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC)

In formulating its response, the government has had Russian oligarchs and corporations at the forefront of its mind. Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Justice Dominic Raab has said: “We won’t let those bankrolling Putin exploit the UK’s legal jurisdiction to muzzle their critics”.

Tom Burgis, journalist and author of Kleptopia: How dirty money is conquering the world, and publisher HarperCollins were sued for the suggestion in the book that ENRC had had three people murdered to protect its business interests. ENRC lost its claim on 2 March 2022 following a preliminary hearing on the basis that only individuals rather than companies can commit a criminal act of murder. ENRC discontinued a second claim against Mr Burgis and the Financial Times for related articles. In giving evidence to MPs, Mr Burgis described the costs of defending the litigation as “the chill – [they] are the weapon”.

(ii) Roman Abramovich

Only 10 weeks earlier, HarperCollins settled a defamation claim brought by Roman Abramovich against it and Catherine Belton, author of Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took on the West. The settlement was made without payment of damages, but such that the text is now corrected or clarified to recognise that the allegation that Mr Abramovich bought Chelsea Football Club at the Russian president’s behest is not a statement of fact. In parallel to this claim, lawsuits were brought against HarperCollins by three other Russian billionaires and Russian energy company Rosneft, two of which were also brought against Ms Belton personally.

(iii) Arron Banks

Judgment was handed down last month in Arron Banks’ defamation claim against author and investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr, which was widely labelled a SLAPP. The claim related to a Ted Talk by Ms Cadwalladr entitled Facebook’s role in Brexit – and the threat to democracy, in which she alluded to lies she said Mr Banks had told about his covert relationship with the Russian government. She later reiterated this message in a tweet when referencing pre-action correspondence from Mr Banks’ solicitors. Interestingly, while the High Court dismissed Mr Banks’ defamation claim on 13 June 2022, it was keen to emphasise that “it is neither fair nor apt to describe this as a SLAPP suit.”

The judge concluded that up until 29 April 2020, Ms Cadwalladr had a public interest defence to her defamatory statements; in other words, there was a public interest in the subject matter and a reasonable belief (based on evidence) that publication was in the public interest. On 29 April 2021, the Electoral Commission accepted the National Crime Agency’s conclusion that there was no evidence Mr Banks received funding from any third party. From then on, the judge held, Ms Cadwalladr had no evidence and reasonable belief Mr Banks had received foreign funding and so could not benefit from the public interest defence. However, Mr Banks failed to establish serious harm to his reputation from the continuing publication. His claim was dismissed, although permission has been granted for him to appeal.

What can be done about SLAPPs?

The Solicitors Regulation Authority was reported last month to have opened more than 20 cases against firms being investigated for possible wrongdoing over SLAPP litigation. Although not many SLAPP claims are issued or litigated against publishers, it is said that these cases are the tip of the iceberg; we should be concerned about the articles never written or published due to the threat of litigation. The government’s call for evidence referenced the Maltese anti-corruption journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who at the time of her murder faced some 40 SLAPP lawsuits.

The current war in Ukraine has undoubtedly focused attention on Russian oligarchs and allies of Vladimir Putin in shutting down reports of corruption. Even when there is no merit to the claims, the costs associated can put off a public interest journalist due to the deeper pockets of their opponents. The counter argument is that there is nothing novel in this use of the legal process. A British company on notice that some dubious practice is to be reported on will also threaten and potentially follow through with litigation. And that is the mischief our procedural regime is intended to address, not least with the early summary judgment and strike-out mechanisms and our costs regime of the ‘loser pays winner’s costs’ principle that is broadly alien in the US.

It is also worth remembering that the pendulum the government believes has swung too far in favour of Article 8 privacy rights did so in part following matters such as the Cliff Richard arrest and the Operation Midland investigation. Both these involved false accusations, with devastating consequences for the public figures involved.

So, while there is doubtless SLAPP mischief being made and reforms may be necessary to address this, we should take a measured approach so as not to throw privacy gains out of the window.

Responses by the European Commission and UK government

The European Commission has issued a proposal for an anti-SLAPP directive under which, if a ‘public participation’ test is met, the action would be subject to a preliminary hearing when the judge would make a detailed assessment as to whether the action is a SLAPP. If at this stage or later it is held to be a manifestly unfounded SLAPP, then cost capping comes into play.

The UK government’s response to the call for evidence looks similar. It says that it intends to introduce a new “statutory dismissal process” to strike out SLAPPs. This will involve a three part early dismissal process, namely the court:

- determining whether it is a public interest publication

- determining whether the case should be classified as a SLAPP, based on one or more criteria being met, and

- conducting a merits test.

There will also be a costs protection scheme. The response is however light on detail, including the absence of statutory definitions of “public interest” and SLAPP. And the proposal for dismissal is for a claim with “no realistic prospect of success”, which is the same test as for the existing summary judgment and strike out mechanisms.

That said, the principle of costs capping, while maintaining our present balancing of Articles 8 and 10 ECHR without a presumption in favour of either, seems the most sensible way forward.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Media Disputes page.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.