On 15 July 2019, David Gauke, the latest in a rapidly revolving cycle of Lord Chancellors, set a new discount rate of -0.25%. It follows the many rounds of consultation, committees and evidence gathering that were rapidly put in motion a month after the announcement of the preceding discount rate of -0.75% in February 2017. In this article, we look at how the new discount rate was determined and what its impact is likely to be for claimants.

The -0.75% discount rate introduced in February 2017 was a long-overdue correction of a 16-year period of manifest under-compensation. While it was a principled application of a longstanding methodology for setting the discount rate, the related increase to the calculation of future loss claims provoked a loud outcry from insurers and institutional defendants. The government then passed the Civil Liability Act 2018, which brought in a new methodology for calculating the discount rate based on a low risk, but not very low risk, portfolio of investments. The new rate based on this new methodology should end over two years of uncertainty, which has stalled the resolution of many serious injury claims.

Predictions for the new discount rate

Since this process of change to the law of damages was instigated, the majority of commentators in the legal and insurance industries had been predicting that the new rate would be somewhere between 0 and 1%. That was in part based on a statement made by Lord Keen, Ministry of Justice (MoJ) Spokesperson for the Lords. However, by the time he appeared before the Justice Select Committee on 1 November 2017, he was clearly having second thoughts about that prediction when he said: “With the benefit of hindsight, it is perhaps unfortunate that the figure was there, but it was just to indicate the direction of travel when you moved the risk element of the portfolio.”

Notwithstanding that note of caution, the industry-wide assumption still appeared to be that the discount rate under the new regime would be a positive number. I appeared to be on my own when I suggested negative discount rates may not be going away anytime soon in my articles for the New Law Journal of 13 April 2018 and 26 April 2019, but that is where we now find ourselves. The new rate of -0.25% is likely to be with us through to the next review, which is due to take place within five years, by 2024.

My optimism that a positive discount rate was not inevitable was largely based on the government’s repeated commitment to the full compensation principle at each stage of this process. In David Gauke’s statement explaining the new discount rate, he refers back to that principle, quoting from Lord Hope of Craighead in the House of Lords decision in Wells v Wells:

“The object of the award of damages for future expenditure is to place the injured party as nearly as possible in the same financial position he or she would have been in but for the accident. The aim is to award such a sum of money as will amount to no more and at the same time no less, than the net loss.”

It is notable that Lord Hope was talking about “the injured party”, because each claimant is only involved in their own claim and their award of damages is to meet their future injury related needs. Unlike insurers, each injured claimant is in no position to spread the cost and risk over multiple claims. In the first of my six articles concerning the discount rate in the New Law Journal, back on 29 September 2017, I posed what I saw as the fundamental question:

“If the law is to change to force seriously injured claimants to take investment risk, the debate needs to look at the flip side of alleged over compensation: What proportion of claimants do we consider it fair to potentially go under-compensated. This fundamental question does not get a mention in the MoJ’s paper.”

It is a huge relief to see that the Lord Chancellor did at least address this question. His answer was one third. He acknowledges that to set a discount rate of +0.25%, at which only half of the claimants saw their damages awards last to meet their assessed needs over their lifetime, would not be full compensation. I agree.

However, he thought it would be a step too far to set a rate of -0.5%, even though that would still leave about 30% of claimants running out of money before the end of their lifetime. So he settled on the rate of -0.25%, which will mean that about one third of claimants will run out of compensation and a worrying 22% would suffer a shortfall of 10% or more. In serious injury claims, this could leave them unable to fund their care and equipment needs for four years or more. Does that sound like full compensation for each of those claimants?

How was the new discount rate arrived at?

So, how did the Lord Chancellor arrive at the new discount rate of -0.25%? The short answer is that he largely followed the expert advice from the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD). Its starting point was to consider the likely annual return on investment from a low risk portfolio. It concluded that this was 2% above Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation.

Next, it deducted 0.75% for the likely costs of investment advice/management charges and tax. Then it considered the impact of inflation on damages, as many aspects of future losses, notably the cost of care, are more likely to increase in line with the long-term trend for earnings than the price of goods. This led to a further reduction of 1% to reflect the mid-point of the difference between CPI prices inflation and earnings inflation. In applying these deductions, the GAD suggested a discount rate of +0.25% would be appropriate if the aim was for 50% of claimants to receive enough compensation to meet their future needs. The GAD suggested a further adjustment down to 0% or -0.5% might be warranted to reduce the proportion of claimants suffering under-compensation. The Lord Chancellor essentially split the difference, opting for the new rate of -0.25%.

What is the impact of the new rate?

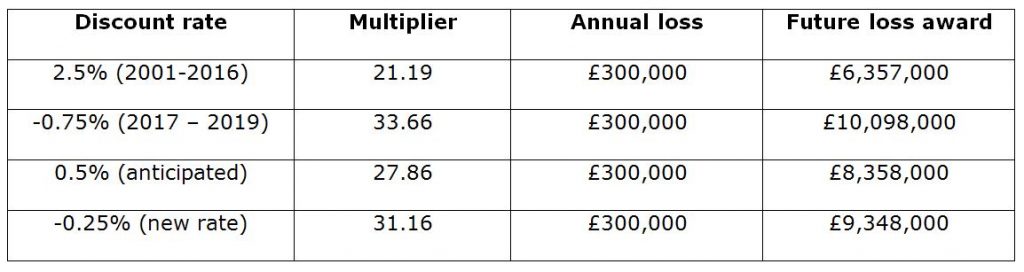

Let’s take the example of a 40-year-old claimant whose serious injury has reduced their life expectancy to a further 30 years and who has estimated future care costs of £200,000 per year and other future losses of a further £100,000 per year. The lump sum future loss awards under differing discount rates would be:

In this example, if the outgoing -0.75% rate represents the best measure of full compensation for this duration and scale of losses, the claimant is arguably under-compensated under the new rate of -0.25% by about £750,000. That is almost four years of their care needs.

However, the claimant would have been about a further £1m worse off if the discount rate had been set at the mid-point of the anticipated range at 0.5%. That £1m shortfall would have left them unable to fund their care for a further five years of their life, likely causing them to fall back on the state to meet their care needs. It is a huge relief that the predictions were not realised, but the new rate ought not to be seen as generous to claimants.

The advice of the Government Actuary’s Department

The GAD has played a valuable role in setting the new rate and it is to be applauded for its efforts. Its report quite rightly sets out a number of the key assumptions made due to a combination of the limitations of the remit it was given and the evidence available. It acknowledges that the predicted level of under-compensation could vary significantly for individual claimants whose circumstances differ from their assumptions.

Longevity

One of the assumptions is that each claimant will live exactly to their projected life expectancy, whereas in the real world 50% of claimants outlive that projection. Consequently, they are at greater risk of their compensation running out before the end of their lifetime. The GAD has throughout acknowledged this longevity risk, but one can only assume the remit it was given did not allow it to factor it into its modelling. Had it done so, it is inevitable it would have shown a greater proportion of under-compensated claimants.

Duration of future losses

The duration of each claimant’s future losses is a further factor that the GAD describes as causing a significant difference. However, it sounds like the MoJ’s call for evidence did not result in a reliable body of data on this important point.

GAD sensibly considered shorter durations of 10 years and longer durations of 50 years, but then adopted a questionable assumed average period of loss of 43 years. That must surely be at the higher end of the wide range of periods for which claimants need to be compensated. The tables in the GAD report show that for those with projected losses of 10 years or less, the majority (over 60%) will be under-compensated. Many of those with the most serious injuries and highest consequent care and other needs have compromised life expectancies. A significant minority are as short as 10 years but far more common are those with claims for the duration of between 10 and 40 years. Unfortunately, the GAD report does not model common loss periods of 20 or 30 years, but the graphs it has published suggest that a fair rate for such periods of loss would be well below the new rate of -0.25% and probably less than the preceding -0.75% rate. This is an important factor when considering the pros and cons of a periodical payment.

A dual rate?

The GAD considered whether a dual rate would be fairer. This would involve one rate for shorter losses and another for longer duration losses. One of the key assumptions underlying this concept is that in the longer term investment returns will be markedly better than the world has experienced in recent times. But will that rosy view of long term returns materialise or are we going to continue to live in economically turbulent times? The truth is no one knows, but why should injured claimants have to bear that risk?

The GAD acknowledges that a dual rate has quite a few practical complications, which would have to be carefully considered before any decision to that effect should be taken. David Gauke’s ministerial statement indicated that this is an issue that should be explored in more detail. This means yet another consultation coming along “in due course”, which is likely to inform the next discount rate review and the work of the expert panel who will be advising him in the run up to that review in five years’ time.

Investment risk and portfolios

The GAD considered the likely return on investment from a low-risk portfolio. It came up with three variants, which it described as “cautious”, “central” and “less cautious”.

Its “cautious portfolio” included 30% of growth assets (mostly equities), the value of which can decrease significantly during economic downturns like the one we have experienced since the banking crisis of 2008. I will leave it to investment advisers to comment on which (if any) of these three portfolios meet the criteria under the Act of being lower risk than would ordinarily be accepted by a prudent and properly advised individual investor.

The “central” portfolio invested over the assumed 43-year period generates a return of 1.9%, which the GAD and Lord Chancellor rounded up to 2% and used in as the start point for setting the new discount rate. Had they taken their start point as the cautious portfolio then the gross return would have been 1.5% and the discount rate would have been 0.5% lower. That, coincidentally, have taken us right back to the -0.75% rate that has prevailed over the last couple of years.

Inflation on damages

Inflation on damages was considered, with the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) replacing the Retail Prices Index (RPI) as the start point. However, the GAD rightly acknowledged that in a number of ways damages inflation is likely to run higher than CPI. Many components of damages are earnings related, notably claims for care and case management, loss of earnings and most aspects of medical treatment and therapies. The GAD acknowledged that earnings inflation usually runs at about 2% higher than CPI and then took a simplified approach by treating all damages inflation at the mid-point between CPI and earnings inflation, that is at CPI +1%. The fact that CPI +1% is broadly equivalent to RPI is a point worth keeping in mind when comparing damages on a lump sum basis with periodical payment options. RPI remains the default position for periodical payments, with indexation to the applicable Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) tables commonplace for periodical payments for future care and other earnings-related heads of claim.

However, the assumption of 50% of damages being earnings related does not really follow the MOJ’s summary of responses to its call for evidence. A number of insurers and the NHS provided evidence showing that the earnings-related heads of losses amounted to somewhere between 70% and 90% of future loss awards for those with the serious injuries warranting awards over £1m. For those claimants, a reduction to the discount rate of a further 0.5% or more would be necessary to truly provide for earnings inflation and deliver full compensation. In any future debate around the pros and cons of a dual rate, serious consideration should be given to mirroring the approach taken with periodical payments and setting a variant discount rate for earnings losses.

Investment charges and tax

The GAD then made a further adjustment for the cost of the investment advice and management, plus tax.

It acknowledged that it has received evidence from a number of those who responded to the MoJ’s call for evidence including the data submitted by the Forum of Complex Injury solicitors (FOCIS), which I summarised in my article for the New Law Journal on 26 April 2019. That data demonstrated the vast majority of the 398 claimants surveyed actually incurred investment management charges in the range of between 1.5-2%. However, rather than rely on evidence of the actual charges incurred, the GAD aligned its allowance for investment charges with their three model portfolios, which they assumed would be passively rather than actively managed, incurring lower fees. The related assumption was that for the claimants who did select active management, it was hoped that the additional charges they would incur would be offset by higher returns.

The adjustment for tax was considered by the GAD to be relatively modest for small or medium-sized claims but did become more significant, at 0.5%, for larger claims, which they categorised as £3m. Most of the claims that we undertake at Stewarts involve serious life-changing injuries and involve claims for £3m or more, sometimes considerably more. Consequently, the overall tax and investment management charge adjustment allowed by the GAD of -0.75% seems to us to be underestimating the reality most of our clients would face. This phenomenon is quietly acknowledged by the GAD, where it indicates a range of tax and investment deductions could be anywhere between 0.6% and 1.7%. Had it adopted a figure closer to the mid-point of that range, that would have caused a reduction of the discount rate by a further 0.25% or 0.5%.

Conclusions

After three Lord Chancellors and a wait of more than two years, we have a new discount rate of -0.25%, which is far better for seriously injured claimants than most industry commentators expected. It also has the advantage of providing a period of certainty, although we can anticipate some further turmoil around the time of the next review in five years.

The mechanism for the five-yearly reviews is one of the positive aspects to have come out of the new discount rate regime. It should at least avoid the unfairness that serious injury claimants faced during the 16-year period between 2001 and 2017.

In the run up to the review in 2024 we may see claimants or defendants trying to either slow claims down to wait for the next discount rate if they think it may be materially better. However, at least we can put the last two years behind us, during which insurers are quite open in acknowledging they simply would not settle claims based on the prevailing negative -0.75% discount rate and, with most of them reluctant to offer periodical payments either.

The Lord Chancellor has restated the commitment to the full compensation principle and has made a modest adjustment to the discount rate to attempt to address the inherent risk of under-compensation in the new methodology. That still leaves a significant cohort (one third) of claimants who will see their money run out and fall back on the state to meet their needs. Each of those claimants will not have received full compensation. In my view, the Lord Chancellor should have made a much larger adjustment to significantly reduce the proportion of those under-compensated. This would probably have taken us full circle to the -0.75% rate that has prevailed since February 2017 and so was perhaps viewed as politically unacceptable.

The position is even more precarious when the assumptions underlying the new rate are closely scrutinised. This will have the greatest impact on the most seriously injured claimants, with expected lifetimes of less than 40 years, whose future losses are mainly for care and other earnings-related losses and whose necessarily larger award are likely to suffer higher taxation.

Closer analysis of the GAD report suggests that for this important category of claimant, who is wholly reliant on their compensation to meet their future needs, a fair rate would have been well under -1%. Even my optimism never extended that far, so perhaps the focus now needs to shift to compelling insurers to make offers on periodical payment options terms alongside any lump sum offers, or at least offer cogent reasons why they cannot or will not.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and teams on our Personal Injury, International Injury and Clinical Negligence pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.