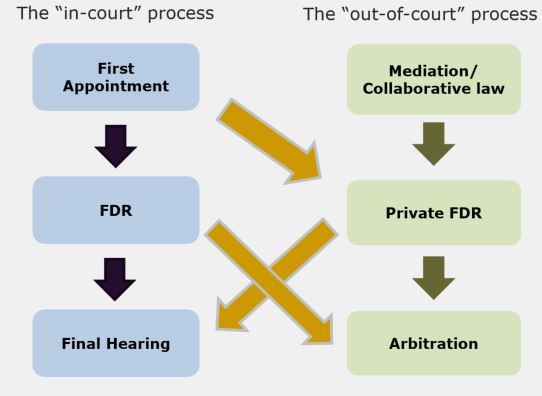

There are now a number of alternatives to the traditional court process, which are increasingly attractive to those who wish to avoid what can often be costly and protracted court-based litigation.

An “out-of-court” process can reduce the time it takes to reach a settlement, save costs and, importantly, reduce stress on the parties (an aspect looked at in more detail by Senior Associate Sarah Havers and Associate Tim Carpenter in their article for Mindset Magazine) An “out-of-court” process can also benefit future communication between the parties, which is particularly valuable if the parties have children who can often be adversely affected by divorce.

This article provides a high-level overview of the “in-court” and “out-of-court” processes to help you to determine which process might be right for you.

The “in-court” process

First Appointment

On making an application for financial relief, a First Appointment hearing will automatically be listed and a court timetable put in place for certain procedural steps to take place before this first hearing. The most important of these steps is the exchange of financial disclosure.

The First Appointment is not a substantive hearing, ie the court will not make any decisions about the outcome of the case. It will, instead, make sure that the court has everything it needs to be able to do so in the future. For example, a judge will decide the following if there are disagreements between the parties about the valuation/computation of assets:

- if questions have been asked of each other’s disclosure, which questions should be answered;

- whether any expert(s) should be instructed to value assets or whether there is a need for expert opinion/specialist advice; and/or

- any other matter relevant to the circumstances, including whether any third parties, such as trustees, should be joined as parties to the proceedings.

The court will also timetable the next hearing, a Financial Dispute Resolution (FDR) hearing.

FDR hearing

This is a “without prejudice” hearing. This means that what is said at this hearing cannot be referred to in later court proceedings. The intention is to encourage parties to put forward their proposals for settlement so that there can be an early resolution of the case.

The judge will evaluate the competing positions advanced by both parties through their legal representatives and indicate the terms of the award they would make were they determining the matter at a Final Hearing. The expectation is that having heard the judge’s view, the parties will negotiate a final settlement (in which process the judge offers to assist). The judge is not thereafter allowed to participate in any future hearings.

Most cases settle at, or shortly after, the FDR. For many involved in litigation, settling at this stage is bittersweet given the stress, cost and time endured by them in contested proceedings.

Final hearing

If a settlement is not reached at the FDR, a further case management hearing may take place before a judge to determine what final preparations need to be undertaken before a Final Hearing. The court will determine how many days of court time the Final Hearing will require. The date for the Final Hearing could be anything from six months to a year away depending on how congested the court list is.

At a Final Hearing, the judge will hear evidence, most often, from the parties themselves. Experts can also be called to give evidence where, for example, there is a continued disagreement between the parties over the value of certain assets.

The judge will decide how the assets should be distributed and whether, for example, any orders for maintenance are appropriate. The terms of the judge’s award are then incorporated into a court order, which is binding on the parties. In a fully contested process, it is not unusual for one or both parties to come away feeling dissatisfied with the judge’s decision. The considerable financial and emotional cost sustained up to this point can add insult to injury.

The “out-of-court” process

Mediation

Mediation is one of the most popular ways to resolve issues arising on divorce or separation. The process usually comprises (in non-Covid times) face-to-face discussions with an independent and expertly trained mediator. However, there is an option to engage in ‘shuttle mediation’, meaning that if you do not feel comfortable sitting in the same room as your former partner or spouse, you do not have to.

In nearly all cases, before issuing an application for financial relief, the applying party will have to declare to the court that they have considered and explored mediation. This is a relatively recent introduction to the process and is intended to help start things off in a non-confrontational and constructive way.

Mediation can be used to resolve any number of issues between the parties, and even complex financial cases can be resolved this way. Third parties such as tax advisers can be present at a mediation, as well as matrimonial lawyers. This can enable the parties to resolve issues surrounding disclosure, which would otherwise be determined at the court-based First Appointment.

Private FDR

The purpose of a private FDR is the same as the in-court FDR process described above. However, the parties can select their judge, who will be an experienced, practising barrister or retired High Court judge. They can also choose their venue, which is usually counsels’ chambers or one of the solicitors’ law firms, making the parties feel more comfortable and at ease.

As the parties choose the judge themselves, and the judge sets aside specific time to read into the case and consider it in detail, the judge’s opinion can hold significant weight in facilitating negotiations. In contrast, in a court process, the parties can sometimes feel as though they are getting ‘short shrift’, being possibly one of several cases that a judge may have to juggle that day. If cases are complex, there may simply not be enough time for a court-based judge to explore the issues and merits of a case properly.

Consequently, a privately instructed judge may better understand the issues between the parties and the nuances in the case, making it more likely for a settlement to be reached.

With a private FDR, the parties can also choose the start time to suit them and avoid lengthy delays waiting around at court. There is a high risk of cancellation of court hearings, which does not happen with private FDRs.

All in all, the private FDR approach is increasingly favoured by parties seeking to achieve an early stage resolution.

Arbitration

Arbitration is a fast track, private and discreet way for parties to achieve finality in the event of disputes.

In a similar way to mediation, the parties select a trained arbitrator. The parties enter into an arbitration agreement confirming that they will allow the arbitrator to adjudicate on the issue(s) between them and make a decision. Unlike a private FDR, the arbitrator’s decision is binding.

An additional benefit to arbitration is that discrete issues can be adjudicated upon. This can help narrow the issues that need to be resolved by the court without incurring further court associated delays. The parties can, much like the private FDR process, select their arbitrator and venue.

Unlike a final hearing, the parties can have greater control over the procedure. For example, they may choose whether the arbitrator will decide the issue(s) on paper or whether there will be a hearing with oral evidence. The timetable is also fixed around the parties’ and their legal advisers’ availability rather than being imposed by the court. This can enable a final decision to be reached much quicker than would be achieved through a final hearing.

Collaborative law

The collaborative approach is based on both parties (and their specifically trained solicitors) agreeing in writing that they will not refer the matter to court for resolution. As a result of this agreement, if one party applies to court, both parties must disinstruct their solicitors and find new representation.

This provides a strong incentive to reach agreement. Collaborative law is based on a series of face-to-face meetings (or now, increasingly via Zoom) to save the cost and tension of negotiating through correspondence where misinterpretations can more easily arise. The meetings are held on a “without prejudice” basis so any discussions conducted in the collaborative process cannot later be referred to in any court hearings. This means that parties can more quickly move to their ‘true’ settlement position.

The collaborative process can be much quicker than a court-based approach. However, depending on the dynamic between the parties, it may not be appropriate.

Conclusion

Toby Atkinson, a Partner and the Divorce and Family Department at Stewarts, says: “Family law is not a ‘one size fits all’ process and a court-based approach will certainly not be appropriate in many cases. The right process will depend on what you want to achieve and your individual circumstances. There are now a range of alternative dispute resolution options available, and clients should be encouraged to consider which of these is most suitable for them and their family.”

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Divorce and Family pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.