The judgment this week in the case of Chaplin v Pistol (1) and Allianz PLC (2)[2020] EWHC 1543 (QB) is an important one for personal injury lawyers as it deals with the issue as to whether parties can introduce life expectancy evidence from statisticians in cases involving shortened lives as a result of injury.

Stephanie Clarke, Partner and solicitor for the claimant, reviews the outcome of the second interlocutory judgment in this case. The first, reported in February 2019, related to lost years claims in calculating loss of earnings in catastrophic injury claims for interim payment applications.

Background

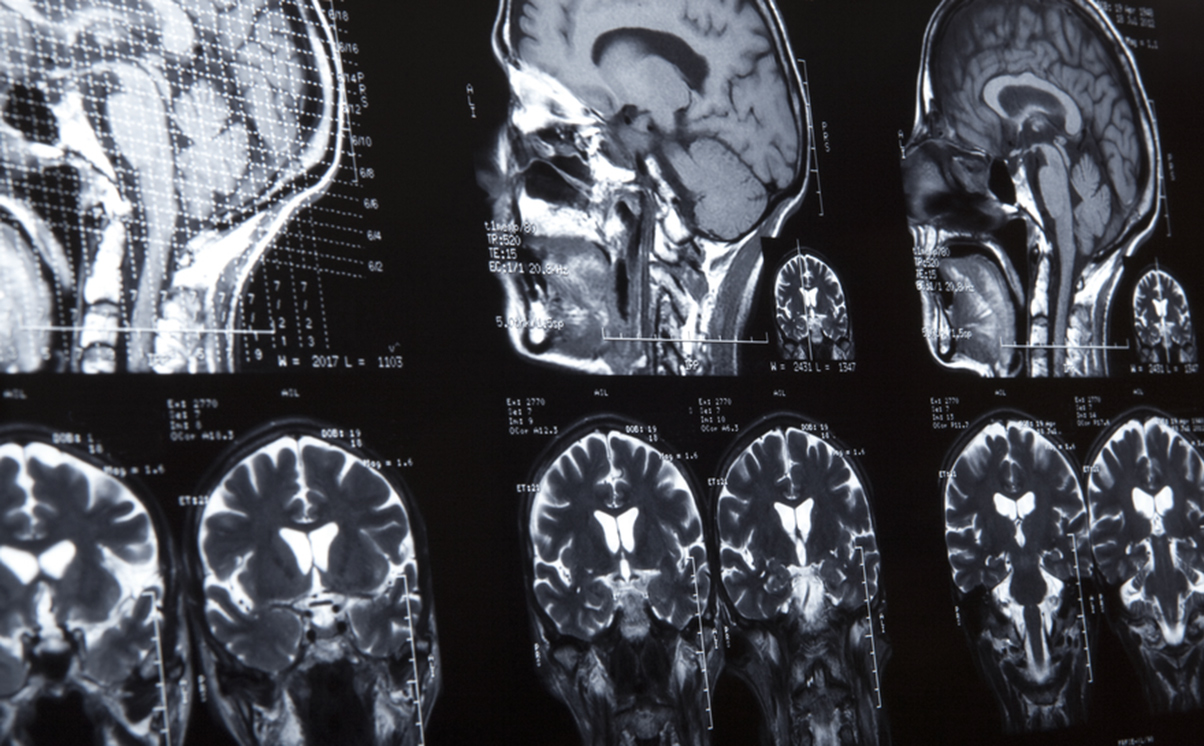

In October 2016, the claimant, Mr Chaplin, sustained catastrophic injuries in a road traffic accident caused by the negligent driving of the first defendant (who was insured by the second defendant). Mr Chaplin, who was aged 28 at the time, suffered a severe traumatic brain injury with tetraplegia and is wholly dependent on others for his care needs. His life expectancy has been considerably reduced. The case is of significant value both in terms of care and loss of earnings. Before the accident, the claimant earned a six-figure salary.

Procedural background

At the time of the defendants’ application, medical evidence had already been exchanged, and joint statements were due one day after the defendant’s application, on 11 June. A joint settlement meeting date had been agreed July, and the case was listed for a 10-day trial with a window starting on 12 October 2020.

The issue of statistical life expectancy evidence had previously come before Master Eastman at the second case management conference in July 2019. At that stage, the defendant applied for permission to rely on expert evidence in the field of medical statistics in the form of a report dated 28 June 2019 co-authored by Professor Strauss and Dr Jordan Brookes. Master Eastman refused that application, and there was no appeal.

The defendants’ current application for permission for further expert evidence

On 21 May 2020, the defendants applied for permission to rely on evidence of two further experts, namely:

- Mr Gary Derwent (an expert on assistive technology), and

- Professor David Strauss (a statistician on life expectancy).

The application in relation to Mr Derwent’s evidence was not opposed.

The hearing proceeded in relation to whether the defendants should have permission to rely on Professor Strauss’s proposed evidence as to the claimant’s life expectancy, using data from three publications written by members of the Californian Life Project:

- ‘Life expectancy of children in a vegetative and minimally conscious state’ – Strauss, et al (2000)

- ‘Life expectancy’ – Shavelle, et al (2007), and

- ‘Long-term survival after traumatic brain injury’ – Brookes, et al (2015).

The judgment

This judgment is highly relevant to all personal injury lawyers. Mr Justice Jay rejected the defendants’ application and in doing so firmly endorsed the view of Master Davidson in the case of Dodds v Arif [2019] EWHC 1512QB about the use of statistical evidence in relation to life expectancy. He also found that they had failed to demonstrate a relevant and sufficient change since their last application when they failed to appeal a decision they did not like and discussed the timing of applications of this kind and the overriding principle.

In that case, after hearing arguments from the defendants in relation to the introduction of bespoke life expectancy evidence, Master Davidson stated as follows:

“For these reasons it seems to me that bespoke life expectancy evidence from an expert in that field should be confined to cases where the relevant clinical experts cannot offer an opinion at all or state that they require specific input from a life expectancy expert (see e.g. Mays v Drive Force (UK) Ltd [2019] EWHC5), or where they deploy or wish to deploy statistical material that does agree on the correct approach to it. This case does not, or does not yet fall into any of categories.”

In the Chaplin case, both medical experts in the field of neurology/neuro-rehabilitation are highly regarded and well established in their field. Dr Clarence Liu was instructed on behalf of Mr Chaplin and Professor Christine Collin was instructed on behalf of the defendants. In his judgment, Mr Justice Jay gives a helpful summary and discussion regarding the statistical data in relation to life expectancy on those with a severe traumatic brain injury.

Mr Justice Jay stated that both parties’ neurological experts had expressed themselves as able without qualification or equivocation to proffer evidence on life expectancy in this case. In addition, there was a relatively narrow gap between them as to the claimant’s future life expectancy. This had been explained, in the main, by the different clinical assessments of the claimant.

Mr Justice Jay confirmed that while there was a difference between the experts, courts are well used to deciding cases on the basis of evidence that is adequate but not optimal. Mr Justice Jay accepted that a seven-figure sum was in issue over the extent of the diminution in the claimant’s life expectancy. Robert Weir QC, for the claimant, asserted that both medical experts essentially had not changed their position since the matter was last heard, which is relevant as set out below.

Use of statistical evidence

It was noted that the defendants’ expert had been aware of the existence of the unpublished data referred to in the Strauss/Brookes June 2019 report and at the time of the last Case Management Conference, she had not indicated that she required the assistance of the medical statisticians on this issue.

The report prepared by Strauss/Brookes in July 2019 was also criticised for drawing attention to further unpublished material not being peer reviewed.

Mr Justice Jay’s judgment sets out the following points:-

- If a party is dissatisfied with the direction of the master, it must comply with Civil Procedure Rule 29 PD6. This provides, in relation to a variation of directions, that a party who disagrees with a court order must either appeal it or demonstrate a change in circumstances since it was made. In this case, Mr Robert Weir QC for the claimant submitted it was incumbent upon the defendants to show a “relevant and sufficient” change in circumstances since July 2019 when the matter was last before Master Eastman.

- Mr Justice Jay indicated that there was no good reason to overturn or criticise Master Eastman for analysing issues between the neurological experts and concluding that the differences between them were largely explicable in terms of different clinical judgment.

- He said that even if the matter had come before him “shorn of any antecedent judicial decisions”, he would still have concluded that evidence from Professor Strauss was not reasonably required for the purposes of Civil Procedure Rule 35.1.

- In reaching this conclusion, he made the following observations:

Although evidence from a medical statistician is, in principle, admissible, ordinarily it should be seen as a starting point for clinical judgments made by medical witnesses (see the Royal Victoria Infirmary and Associated Hospitals NHS Trust v B (a child) 2002 EWCA7348 at paragraphs 20 and 39).In particular, he confirmed that medical experts are usually well able to apply and interpret quite complex statistical evidence. This can be admitted as hearsay if set out in a published paper that has been peer reviewed, without the need to call purposeful explanatory evidence.The defendants’ expert did not say that specific input was required from medical statisticians for her to assess the claimant’s life expectancy, although she did say that input would be desirable because it would give the court greater confidence in it’s conclusion. Mr Justice Jay found that courts are very used to deciding cases on the basis of evidence which is adequate but not optimal.If the defendants wished to introduce statistical evidence, they should have done so much earlier in the litigation so that both experts could address this before committing themselves to their conclusions.He drew attention to the fact that Professor Strauss did not appear to be prepared to disclose his group’s unpublished data and that this data has not been peer reviewed. Furthermore, Counsel for the defendants argued that the claimant would be bound to accept it as “authoritative and reliable”. There is an obvious unfairness inherent in one party’s expert relying on data which the opposing party is unable to examine.The defendants’ submission that the neurologists were not in agreement as to the correct approach to the statistical evidence was found to be unpersuasive. The judge found that there was substantial agreement provided one excludes from consideration the unpublished data referred to in the 2019 report. - Finally, Mr Justice Jay considered whether the evidence of Professor Strauss should, in any event, be excluded in exercise of his discretion as coming too late in the day. He referred to the case of Taleb v Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust [2020] EWHC 1147, which confirms that applications of this nature fall to be determined in line with the overriding objective. He rejected the defendants’ submission that the introduction of statistical evidence was unlikely to delay the trial. He referred to the claimant and claimant’s family situation and agreed it would be intolerable to adjourn the trial even if he found that there was a sufficient change in circumstances, which he had not, since directions were made in July 2019.

Conclusions

The defendants are unlikely to have raised this issue had it not been for the high value of loss of earnings together with the parties’ differing views of life expectancy and its impact on the future multiplier.

Hopefully the issue of Defendants arguing for the introduction of life expectancy evidence from Professor Strauss and Dr Brooks, who rely in part on unpublished data which has not been peer reviewed, will now be limited to a very small proportion of cases.

While care and case management will likely be dealt with by Periodical Payment Orders, the claimant was a highly paid banking employee at the time of his accident, and the multiplier in relation to life expectancy for loss of earnings will have a significant impact on his future loss of earnings claim.

Counsel and solicitors for the claimant: Rob Weir QC Devereaux Chambers and Stewarts

Counsel and solicitors for the defendants: Ben Browne QC 2 Temple Gardens and BLM Manchester office.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Personal Injury pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.