Action for Brain Injury Week, organised by the brain injury association Headway, takes place from 19 to 25 May 2025. This year, Headway is highlighting the fluctuating and unpredictable nature of a brain injury and the gap between a person’s capabilities on a good day versus a bad day.

Partners Nadia Krueger-Young and Scott Rigby spoke to some of our clients and their families (names have been changed for anonymity purposes) about their experiences of good and bad days managing a brain injury. Amy Fielding, a partner at Stewarts, also shares her perspective as the daughter of a mother who sustained a serious brain injury following a stroke.

Jason’s story

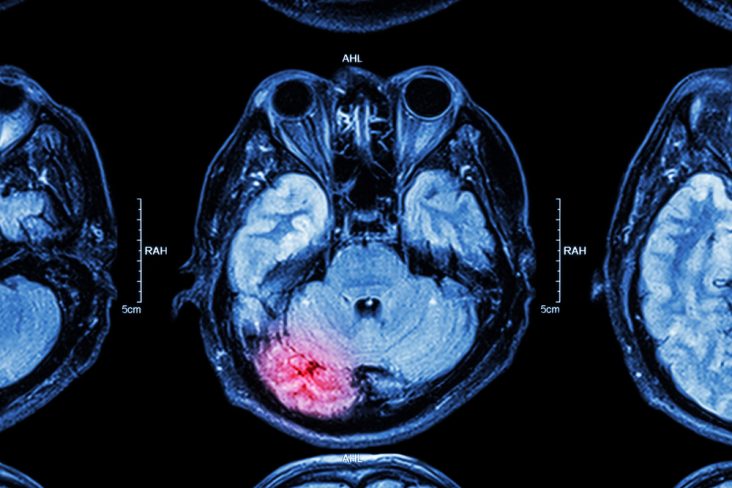

Seven years ago I had a major stroke, which left me with lifelong disability down my left side. I spent four months in hospital rehabilitation, building up my strength, learning to walk again and preparing to re-enter the world.

Early on, there were many dark days as I struggled to come to terms with the huge physical and mental challenges that living with a stroke presents.

Most obvious is the crushing fatigue. Because your brain can no longer engage all the muscles available, hauling a disabled body around feels like you’re permanently carrying a sack of heavy weights. Then there is the relentless frustration of being unable to carry out the most basic tasks because now you only have one working hand. Immediately, life’s daily rituals – washing, dressing, cooking, popping to the shops – become fiendishly complicated and time-consuming.

The mental challenges were even harder to deal with. The fatigue saps your energy and eats away at your mood. Depression was a constantly lurking spectre. I was grappling with a profound sense of loss. Gone, I thought, were my independence, identity and feeling of self-worth. Once a keen runner, now I could only stare jealously at the toned joggers chugging around our local common. It broke my heart to discover I could no longer hold my cherished guitar, let alone play it. A fear of falling and smacking my head on the pavement whenever I went out also dogged my morale.

I soon found social situations, particularly large ones, very stressful. Meeting new people at parties became anxiety-inducing, as I could no longer perform the instinctive social niceties that come with being introduced to someone. Shaking hands, I’d either drop my walking stick or knock someone’s glass flying as my awkwardness let rip. Explaining to so many well-meaning people that I am not ‘better’ just because I’ve left hospital was a repeated irritation.

Seven years on, I can now say the good days outnumber the bad. Having the support of a loving family throughout my journey has been a lifesaver. I’ve generally followed the therapists’ advice – recognising the role that thoughts, feelings and actions have on mood. I try to keep active (I can just about ride an exercise bike at the gym) and regular walks form part of my regime. I still get fatigued, but less often, and I really do find that exercise and getting outside on the dark days helps lift my mood.

I can still enjoy socialising, but now mostly in small groups with family and close friends who understand my situation. One continued unwelcome legacy of my condition is post-stroke emotionalism, the involuntary habit of bursting into tears or hysterical laughter at some funny or moving news/event. Neither of which are very cool.

I’ve been on a slow journey of acceptance and adjustment. I’ve gradually learnt to shift my outlook from bemoaning “what I can’t do” to working out “how am I going to do that?” What’s more, I no longer stare enviously at the toned joggers. Instead, I comfort myself with the belief that what I’ve achieved since my stroke has been impressive.

James’s story

I sustained a brain injury a few years ago as a result of a road traffic accident. I am told I have made a very good recovery, but my life now is a mix of good days and bad days. It’s a journey of resilience, adaptation and constant learning, and no two days are exactly alike. The ups and downs can feel like an emotional and physical rollercoaster.

Bad days can hit me hard, often without warning. Intellectual struggles are a common challenge for me, with brain fog making it difficult for me to focus, process information or make decisions. Tasks that once felt second nature to me, like following a recipe or writing an email, can feel overwhelming. Memory lapses can mean forgetting a conversation from moments ago or misplacing a vital item. These moments lead to frustration and, on occasion, helplessness.

On bad days, emotional difficulties are often accompanied by cognitive struggles. Mood swings and anxiety make it harder for me to connect with my friends and family. Social situations can feel exhausting, sometimes leaving me feeling isolated and misunderstood. Bad days do make me feel very vulnerable, but I try to remind myself there’s positivity in learning how to recognise and accept these moments as part of the healing process.

Then, there are the good days. These are the days when everyday challenges feel a little lighter and easier. They are moments of clarity amidst the fog when I can remember things that normally escape me, or I can focus on a task for longer than usual. Small victories, such as recalling a name, building stamina during a therapy session or simply making it through the day without feeling fatigued, can feel like an amazing achievement. It’s these days that offer me hope and remind me of the progress I have made, however gradual it may feel sometimes.

My good days are often boosted by support and self-care. A kind word from a friend, an act of compassion or just a quiet moment of joy can make all the difference. These days help me to rebuild confidence, showing that improvement, however small, is possible. Each step forward, no matter how tiny, serves as a reminder of the resilience and strength I possess.

Living with a brain injury often means learning new ways to approach tasks and challenges. I have learned that on bad days, it’s okay to slow down. Creating a structure for my daily routine helps me to minimise feeling overwhelmed, while tools like reminders, calendars or apps help with my memory and organisation. I have found that giving myself permission to rest when necessary is really important in managing my fatigue and emotional well-being.

On both good and bad days, the support system I now have, through my case manager, is a lifeline. Family, friends, support workers and my therapists all provide important encouragement, whether it’s to celebrate my progress or to offer me comfort during setbacks. I have learned to celebrate my victories, no matter their size, and I try to be kind to myself on harder days. I have discovered that healing isn’t continuous; it has ups and downs, and accepting that can help ease the pressure of expectations.

Living with a brain injury is not an easy path, and certainly not one I would have chosen. It is a testament to the strength and adaptability of the human spirit. My bad days feel heavy, but my good days are like a beacon of hope and progress. Having spoken to other brain injury survivors, I understand that each person’s brain injury recovery is unique, but I think the common thread is resilience. Whether you’re someone living with a brain injury or supporting a loved one, remember the power of compassion, patience and hope. Every step forward, no matter how small, is worth celebrating.

Karen’s story

My daughter sustained a brain injury in a road accident almost 10 years ago. When Eva’s injury happened, I felt so utterly helpless. I didn’t know how best to support Eva. I just wanted to make her better, but I didn’t know where to begin.

Over time and through experience, I have learned that supporting a loved one who has suffered a brain injury requires patience, understanding and adaptability. It’s a journey with both bright moments and challenging days, and the right support can make a significant difference.

On good days, we celebrate the small victories together. If Eva feels up to it, I encourage her to engage in activities that bring her joy or help her reconnect with things she loves like listening to music, cooking her favourite meal or chatting with her friends. Encouraging Eva’s independence, even in small ways, can boost her confidence and sense of normalcy. I’m there to cheer her on, but I also stay attentive to signs of overexertion.

On difficult days, I try to focus on providing emotional support and comfort. Brain injuries can cause frustration, fatigue and mood swings, so I try to offer a calm and reassuring presence; sometimes, just sitting quietly together can help. It is important to listen without judgment if Eva wants to talk. I gently remind her that it’s okay to have setbacks, and I encourage self-care whether it’s resting, hydrating or practising relaxation techniques.

For both kinds of days, clear and consistent communication is key. I ask Eva what she needs, and I adapt my approach as circumstances change. Above all, I acknowledge Eva’s resilience while making sure I take care of myself so I can continue to provide steady and compassionate support to Eva on her journey following her brain injury.

Amy’s story

I was extremely fortunate to have been brought up by a trailblazer of a mum, a fiercely independent and driven woman from working class roots whose largest belief was that through hard work and determination, anything was possible. She didn’t tolerate fools gladly but always had an intense need to care for those close. After training as a nurse and then a midwife, she recognised a dire need for community care for the elderly, which led to her establishing the first residential nursing home in Lytham St. Annes, Lancashire, in 1984. From this home, hundreds of others opened in the decades that followed. In the later years of her life, many people who worked with her would frequently share stories about how much of an inspiration she had been and how grateful they were for what she had achieved by trying to create this as a ‘home away from home’.

After travelling the globe for close to a decade after retirement, she sadly had a stroke in 2016. Regrettably, this was rapidly followed by another more serious brain injury, caused by an admitted failure by the hospital to give her blood thinners in the weeks after her stroke. A blood clot formed, depriving her brain of oxygen. After life-saving surgery, Mum woke up in the ICU a very different person to what she was before. The tour de force of a person that everyone still speaks of with pride and fondness had sadly disappeared.

The reality of someone living with any injury, but particularly a brain injury, is that it’s incredibly difficult to predict what is going to happen. The injury itself and what that takes away is hard enough but it’s the ongoing daily challenges which are the most difficult. There’s also no ‘one size fits all’. No one injury presents itself in the same way for the person it affects. Just as each person is unique and has their own behaviours and personalities beforehand, the way their injury manifests is similarly unique. Many behaviours or habits that the person had before exhibit in more extreme ways. I realised quickly that it was key to try to understand and best manage this by knowing Mum almost as well as I knew myself. The nine years were an evolution of a very different relationship between us. But it was only because of her strength and how she had brought me up that I was up to the job.

On the good days, she could be incredibly happy and content. She would be full of smiles while largely gorging on cakes, ice cream and chocolate. Her wicked sense of humour would surprisingly spill out, often taking people by surprise. It seemed that on those days, she often thought of herself as being much younger, with no responsibilities or cares in the world. She could be as much fun as she had always been. These days were a blessing and allowed us to see glimmers of hope and light.

On the bad days, conversely, she seemed to understand that something terrible had happened but not quite what or why. On those days, she could rant, rave, scream or lash out, often repeating over and over that she was very scared. It was on these days that even trying to leave the room would cause great distress and anguish. For all involved, those days took incredible strength and resilience to manage.

There were also the quiet days, and sadly, these became more frequent as the years passed. On those days, she would sleep for long periods, and it was unclear if she knew if people had visited or what was going on around her. Her always intensely inquisitive (and let’s be honest) nosey nature was vanishing, and she was very much in her own little world of silence. I suspect those days were much harder for those around her than for her.

Nick’s #LifeBeyondInjury story – enjoying family life after a brain injury

Nick was injured while on his motorcycle, and sustained orthopaedic injuries and a severe brain injury. In this video Nick and his mother tell his story, alongside Stephanie Clarke, a partner in our Personal Injury team.

Find out more

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and teams on our Personal Injury, Medical Negligence and International Injury pages.