As dispute resolution mechanisms grapple with the ongoing fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, entities are considering alternative options to avoid potential inefficiencies or anticipated bottlenecks in the courts. One option is to refer disputes to arbitration. In this article, we examine tribunals’ powers in relation to evidential orders and how these can be supported or supplemented by the courts.

Arbitration is a consensual and flexible process to resolve disputes in a legally enforceable manner outside the courts. It is already the favoured mechanism of dispute resolution for a number of industries, particularly those operating across borders.

In evaluating the merits of a referral to arbitration, parties will weigh up the well-versed advantages of arbitration against the potential disadvantages (whether perceived or otherwise) of having a dispute resolved by a tribunal rather than by the courts.

One consideration may be the suggestion that tribunals are unwilling or unable to make orders, or sanction parties that wilfully flout or ignore orders, with the same weight and willingness that a court could in litigation proceedings. This can be particularly important in the context of disputes between parties about evidence, such as which documents have to be produced to the other side. The question of the scope of a tribunal’s powers is, therefore, of paramount importance.

Recent case law has brought into focus the interplay between a tribunal’s powers and the court’s supportive role in the context of obtaining evidence from obstructive opponents or third parties. To test the suggestion raised, in this article, we will consider whether the perception that the tribunal lacks the teeth to grant or enforce evidential orders is fair.

Evidential issues: the powers of the tribunal and the court

Arbitral tribunals in proceedings seated in England and Wales have wide discretion to make orders relating to evidence. This discretion derives from the Arbitration Act 1996 (the “Act”), which provides at section 34(1) that “it shall be for the tribunal to decide all procedural and evidential matters”.

In addition to the Act, the rules and procedures that govern an arbitration are commonly supplemented by institutional arbitration rules (such as the rules of the London Court of International Arbitration). Those rules are usually even more expansive than (or at the very least reflective of) the Act in terms of a tribunal’s powers and discretion. Given the variety of institutional rules that may apply, in this article, we will only consider the base level position under the Act. Parties should, therefore, be aware that a tribunal’s powers may be, and are usually, further supplemented under any applicable institutional rules.

To promote compliance with a tribunal’s discretion to make orders regarding evidence, section 40(1) of the Act obliges parties to “do all things necessary for the proper and expeditious conduct of the arbitral proceedings”. Section 40(2)(a) of the Act confirms that this applies to compliance “without delay with any determination of the tribunal as to procedural or evidential matters”. This obligation, coupled with a tribunal’s broad discretionary powers, is usually sufficient to ensure party performance of obligations and to ensure adherence to day-to-day procedural and evidential issues.

Why? Because, just like in any contentious proceedings, a party will not want the arbiter of the dispute, whether a judge or an arbitrator, to exercise their powers to, for example, draw adverse inferences from a party’s failure to comply.

However, disputes can (and do) arise in respect of matters of evidence, for example, where a party objects to disclosing certain documents, or where there is a dispute about the form or scope of witness evidence. In those instances, a tribunal can make specific evidential orders, utilising its general discretions under sections 34 and 38 of the Act.

For example, a tribunal can make orders:

- requiring parties to disclose documents;

- obliging parties to preserve evidence; and/or

- in respect of witness evidence (for example, as to the form of such evidence or as to witness attendance at a hearing).

In addition to the powers of the tribunal, the Act provides for the English courts to have ancillary supportive powers. These powers can be deployed to provide further support to the tribunal and the arbitral process. These court powers can help fill the gaps in the tribunal’s powers on occasions where either:

- the tribunal cannot make the order required (for example, a tribunal cannot make orders against third parties who have not submitted to the arbitration); or

- the tribunal is unable for the time being to act effectively (for example, at the earliest stage of the arbitration when the tribunal has not yet been constituted).

On these occasions, the Act enables the courts to make enforceable orders in support of the arbitration. For example, under sections 43 and 44 of the Act (and reflective of the tribunal’s powers), the court can order parties to the arbitration to disclose documents, preserve evidence or summon witnesses.

Importantly, sections 43 and 44(2)(a) of the Act enable the court to make orders against third parties, filling the procedural gap left by the fact that the tribunal’s powers are limited to parties to the arbitration. In particular, in certain circumstances, the court can order:

- a third party witness to attend an arbitration hearing to give oral testimony;

- a third party to produce specifically identified documents in the arbitration proceedings; and/or

- the taking of evidence from third-party witnesses (ie, to provide a deposition) for use in the arbitration.

Whether or not the court can or will make such orders depends on the facts of the case (for example, dependent upon where the arbitration is seated), the provisions of the Act (for example, in certain circumstances the agreement of the parties or the tribunal’s permission is required) and the court’s discretion.

Sanctions for breach of orders

Having established that a party broadly has the means to obtain evidential orders (whether from the tribunal or the court) in respect of arbitration proceedings, parties may nonetheless remain concerned that these orders cannot be enforced in the same way that a court order in litigation proceedings could be.

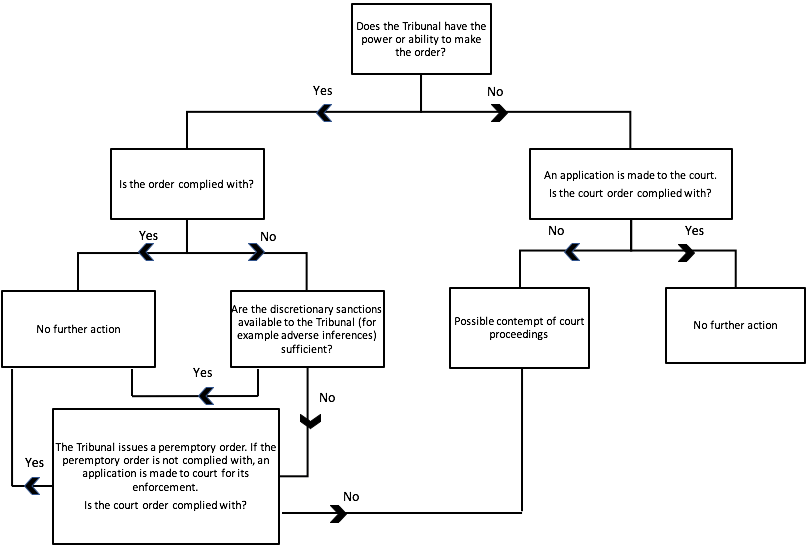

The starting point is that parties are obliged to comply with any order made against them. However, as is the case with all contentious proceedings, opposing parties may be disinclined to comply with a tribunal’s orders. Instead, they may adopt an obstructive or uncooperative stance, for example, by refusing to provide documentary evidence within the correct timeframes, or at all. In those circumstances, two principal avenues in arbitration can be pursued (either separately or together):

- practical sanctions or measures that can be applied by the tribunal; and/or

- enforcement of a tribunal’s peremptory order via the court.

Practical sanctions or measures

In reality, parties are likely to comply with a tribunal’s orders voluntarily and will be reluctant to wilfully flout orders as that will leave a poor impression with the tribunal. The tribunal has the discretion to take a variety of steps that penalise non-compliance and/or incentivise future compliance. It is free to draw its own conclusions and exercise its own discretion on an ad hoc basis with respect to a parties’ sustained default.

As a second step, in cases of more serious non-compliance, the tribunal may also have recourse to the Act. In certain circumstances, section 41(3) of the Act entitles a tribunal to dismiss a defaulting claimant’s claims if the breaches of its orders constitute an inordinate and inexcusable delay on the claimant’s part in pursuing the claim. If the defaulting party is not a claimant and/or the default is not serious enough to warrant a total dismissal of the claims, but there is nonetheless no sufficient cause to explain the lack of compliance, a tribunal can instead issue what is known as a peremptory order. This is a final chance for a defaulting party to comply within a prescribed timeframe. If a party still refuses to comply, section 41(7) of the Act empowers a tribunal to do one or more of the following:

- exclude evidence (ie, exclude from evidence documents or testimony submitted late so that the defaulting party cannot rely on any allegation or material that was the subject matter of the orders);

- draw adverse inferences (ie, a tribunal may draw appropriate or adverse inferences from a party’s non-compliance, for example, infer its own conclusions as to why a party may be refusing to disclose apparently relevant evidence or making witness testimony available on time);

- proceed to make an award on the evidence before it;

- award adverse costs (ie, penalise a defaulting party by an award of costs against it, including indemnity costs, irrespective of its success or otherwise in the arbitration).

Enforcement via the court

In addition to the practical sanctions or measures outlined above, if a party remains in breach of a peremptory order, the court’s supervisory powers can also be utilised by way of an application under section 42 of the Act to the court for an order requiring compliance. If the court orders enforcement of the peremptory order, continued breaches may result in contempt of court proceedings against the recalcitrant party (which could result in fines or custodial sentences). These are the same sanctions that would exist if the dispute was proceeding in litigation before the courts.

As outlined above, tribunals do not have the power to make orders against third parties. So, a court order may have to be sought, for example, if a third party is in possession of documents that are material to the issues in dispute in the arbitration. In those circumstances, a third party’s continued breach of a court order requiring, for example, the witness to attend the arbitral hearing and provide evidence, could be penalised by contempt of court proceedings as the court has already exercised its coercive powers.

By the above mechanisms, a party in arbitration has at its disposal a collection of options to seek to ensure compliance with a tribunal order, as is illustrated below:

Conclusion

Tribunals do not have identical powers to the courts in respect of the orders they can make and their coercive powers. However, that does not mean a tribunal cannot, either independently or with the court’s support, achieve the same or similar outcomes. Tribunals have a variety of powers, sanctions and measures at their disposal to both make and ensure compliance with evidentiary orders. Moreover, courts in England and Wales are generally pro-arbitration and can, and often do, exercise their supervisory powers in support tribunals and the arbitral process.

In principle, there is little truth to any suggestion that a tribunal does not have at its disposal the powers necessary to conduct arbitral proceedings appropriately when it comes to questions of evidence and procedure.

In practice, the reality may be very different. Parties should consider the practical effect and likelihood of seeking the court’s coercive powers. Technically, recourse can be had to contempt of court proceedings, but in most commercial disputes that is unlikely to be necessary. Of far more importance to parties will be the practical and immediate steps a tribunal can take when faced with an obstructive party. Usually, it will achieve a party’s objective if a tribunal draws adverse inferences from a defaulting party’s conduct or attaches little (if no) weight to a claim or defence that a party has refused to provide evidence to substantiate. Although the court’s intervention can be sought, in practice this is rarely necessary to a fair resolution of the dispute. In that respect, the fact of the tribunal’s different powers may present no meaningful or practical disadvantage for prospective users of arbitration. This is borne out by the popularity of arbitration as a means of dispute resolution.

If a party is considering submission of a dispute to arbitration but is unsure as to whether the tribunal may be empowered to take steps anticipated as necessary during the proceedings, it would be sensible to seek advice on the relevant provisions of the Act, and any applicable arbitration rules (which we have not considered in this article), to ensure that the tribunal’s powers are being fully utilised. For example, parties may mistakenly believe that a tribunal cannot sanction a witness who is found to have lied in the same way that a court can. If that is a concern, a party could seek the tribunal’s exercise of a power under the section 38(5) of the Act to determine that a witness must give evidence on oath. Dishonesty in these circumstances can have consequences just as serious as before the courts, including contempt of court.

Covid-19 is impacting individuals and companies around the world in an unprecedented way. We have collected insights here to help you navigate the key legal issues you may be facing at this time.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our International Arbitration page.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.