Partner in our International Injury team Scott Rigby and Sarah Prager, a barrister at 1 Chancery Lane, examine whether it’s time to revisit the concept of ‘bodily injury’ within the meaning of the Montreal Convention.

Relevant provisions of the Montreal Convention

The Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air done at Montreal on 28 May 1999 (“the Convention”) was ratified by the United Kingdom on 29 April 2004 and came into force on 28 June 2004 by reason of the Carriage by Air Acts (Implementation of the Montreal Convention 1999) Order 2002, itself provided for under s.8A of the Carriage by Air Act 1961 and s.4A of the Carriage by Air (Supplementary Provisions) Act 1962. It is implemented across Europe by way of Regulation (EC) No.2027/97, as amended by Regulation (EU) No.889/2002.

Pursuant to Article 29 of the Convention, in the carriage of passengers, baggage and cargo, any action for damages, however founded, whether under the Convention or in contract or in tort or otherwise, can only be brought subject to the conditions and such limits of liability as are set out in the Convention. In any such action, punitive, exemplary or any other non-compensatory damages are not recoverable. Essentially, then once a passenger embarks on a flight, he or she may claim damages for personal injury only under the Convention and not in breach of contract or negligence (see in this regard the decision of the Court of Appeal in Sidhu v British Airways [1995] 1 WLUK 521).

Article 17 of the Montreal Convention provides that:

“The carrier is liable for damage sustained in case of death or bodily injury of a passenger upon condition only that the accident which caused the death or injury took place on board the aircraft or in the course of any of the operations of embarking or disembarking.”

This echoes the equivalent provision of the Warsaw Convention, from which the Montreal Convention was derived:

“The carrier is liable for damage sustained in the event of the death or wounding of a passenger or any other bodily injury suffered by a passenger, if the accident which caused the damage so sustained took place on board the aircraft or in the course of any of the operations of embarking or disembarking.”

In both cases, the carrier is liable only for bodily injury. Does this cover emotional or psychological injury?

Caselaw under the Warsaw Convention

The answer to this question was definitively provided by the House of Lords under the Warsaw Convention regime.

The court relied heavily on the decision of the United States Supreme Court in Eastern Airlines Inc v Floyd (1991) 499 US 530, which arose out of a claim for emotional injury sustained after flight crew announced that ‘the plane would be ditched’, after which rather alarming statement, the engine was restarted and the plane landed safely.

The Supreme Court held: “We conclude that an air carrier cannot be held liable under article 17 when an accident has not caused a passenger to suffer death, physical injury, or physical manifestation of injury. Although article 17 renders air carriers liable for ‘damage sustained in the event of’ (‘domage survenu en cas de’) such injuries . . . we express no view as to whether passengers can recover for mental injuries that are accompanied by physical injuries. That issue is not presented here because respondents do not allege physical injury or physical manifestation of injury.”

At one point, however, it appeared that what was then referred to as ‘nervous shock’ would fall within the definition of bodily injury; in Georgopoulos v American Airlines [1993] Cup Ct NSW, 10 December 1993, the High Court of New South Wales found that the Anglo-American concept of ‘bodily injury’ encompassed nervous shock, and so a claim could be brought for the latter under the Warsaw Convention.

In the American case of Weaver v Delta Airlines (1999) 56 F Supp 2d 1190, the claimant claimed for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) arising from an emergency landing. The uncontradicted medical evidence was that extreme stress could cause actual physical brain damage, and the judge observed that ‘fright alone is not compensable, but brain injury from fright is’. The claimant recovered damages on the basis that she had proven a physical injury to her brain, which had manifested itself as PTSD. The decision was followed in In re Air Crash at Little Rock, Arkansas (2000) 27 Avi 18.

The House of Lords in King v Bristow Helicopters; Re M [2002] 2 WLR 578 put an end to the speculation, but only temporarily. In Re M, the claimant had been sexually assaulted while on a flight operated by the defendant carrier and had experienced a major depressive illness as a result. In King, the claimant developed post-traumatic stress disorder and then a peptic ulcer after being a passenger in a helicopter which had almost crashed due to engine failure.

The majority of the House (the exception being Lord Hobhouse) rejected the line of authority deriving from the decision in Weaver and found that it was wrongly decided and should not be followed. Lord Hobhouse, by contrast, found it ‘wholly unexceptionable’.

Lord Steyn referred to the travaux preparatoires to the Montreal Convention as raising the possibility of some limited recoverability for mental illness in the future but did not provide particulars of how that might look. For what it is worth, the relevant House of Commons Written Answers for 3 July 2000 (Col 87W and Col 88W) state as follows:

“Montreal Convention

Mr Dismore: To ask the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions what representations he has made in relation to the Montreal Convention to ensure UK passengers will be able to claim compensation for psychiatric injury caused by air accidents; and if he will make a statement. [128317].

Mr Hill: Damages for mental injury caused by air accidents are already recoverable in the UK when associated with physical injury. In preparation for the Diplomatic Conference held in Montreal in May 1999, at which the Convention was signed, the UK supported a proposal by Sweden for a separate head of claim for mental injury. Prior to the Conference, however, that proposal was withdrawn from the draft text of the Convention. Our position was that a separate claim for mental injury could be advocated only if there was sufficient support to gain global agreement. There was not sufficient support so, in the interest of securing the best deal for the UK, it was decided to support the text of the Convention without a separate reference to mental injury. The Conference ‘travaux préparatoires’, nevertheless, indicate that damages for mental injury can be recovered in certain states and that jurisprudence in this area is developing.”

This raises more questions than it answers, however; it is beyond doubt that international conventions must be interpreted harmoniously between the various signatory states, insofar as it is possible to do so. The fact that some states, including the UK, have for years been prepared to compensate mental injury, whereas others are not, does not assist a claimant who is forced to make a claim under the Montreal Convention, which does not appear to found a claim in such circumstances.

Lord Nicholls took the view that it was all a question of medical evidence; if the expert evidence showed that there had been an injury to the brain, damages would be recoverable. Lord Mackay agreed, commenting that the question to be determined was whether the evidence demonstrated injury to the body, including in that expression the brain, the central nervous system and all the other components of the body. If it did, the injury would be compensable.

Lord Hope said that he would be inclined to read the phrase in a way that would confine its application to ‘an injury to the skin, bones or other tissues of the body and exclude mental injury’, but agreed with Lord Mackay that if expert evidence showed that the psychological injury was due to an injury to the brain, the passenger could recover for it; and considered whether to remit the claim in M to the court below for consideration of whether her depression could be proven to be due to physical changes in her brain, but decided not to do so for procedural reasons. He added“…I would venture to suggest that one would expect an injury falling within the expression ‘bodily injury’ to be capable of being demonstrated by an examination of the body of the passenger, making the best use of the most sophisticated means that are now available…”

According to Lord Hobhouse, who appears to have been considerably more sympathetic than his brethren to a claimant-friendly interpretation of the Convention: “…bodily injury simply and unambiguously means a change in some part or parts of the body of the passenger which is sufficiently serious to be described as an injury. He continued: “It does not include mere emotional upset such as fear, distress, grief or mental anguish… A psychiatric illness may often be evidence of a bodily injury or the description of a condition which includes bodily injury. But the passenger must be prepared to prove this, not just prove a psychiatric illness without evidence of its significance for the existence of a bodily injury…

“there is respectable medical support for the view that, for example, a major depressive disorder is the expression of physical changes in the brain and its hormonal chemistry. Such physical changes are capable of amounting to an injury and, if they do, they are on any ordinary usage of language bodily injuries. The passenger needs to prove by qualified expert evidence that these changes have occurred, that they were caused by the accident and that they have led to the psychiatric condition which constitutes the damage complained of. If he discharges this burden of proof he has satisfied the requirements of the Article…”

In the end both claimants failed in their claims, because neither of them had adduced expert evidence to the effect that their psychological disorders were caused by physical alterations to their brains. In the opinions of all the Lords but Lord Steyn, had they done so, they could have succeeded in their claims.

The consequences of the decision in King v Bristow Helicopters; Re M

The decision in King v Bristow Helicopters gave rise to some strange results. Where a claimant acquired life-altering PTSD as a result of a highly stressful situation, such as a hijacking or emergency landing, he or she recovered nothing; but where a claimant sustained a transient bruise or other modest physical injury, the claim could succeed.

In Glen v Korean Airlines [2003] 3 WLR 273 witnesses to an air crash were able to recover for psychiatric injury where they could show that they were primary or secondary victims within the common law definitions of those terms. If, therefore, an aircraft crashes, but the passengers escape physical injury, following King v Bristow Helicopters, onlookers with a close connection with those passengers would be able to recover for psychiatric harm, but the passengers would not; or at least, not unless they adduced expert evidence to the effect that their psychiatric symptoms are due to physical alterations in the structure of their brains.

Almost two decades have passed since the decision of the House of Lords, and the state of scientific and medical knowledge has advanced considerably, yet still the higher courts have not been called up to revisit the issues raised in the case. It appears that practitioners, having understood that ‘the Warsaw Convention (and by extension the Montreal Convention) doesn’t compensate for psychological injuries’, have chosen not to bring claims arising out of such injuries sustained in the course of transportation by air. Is it time to reconsider this approach?

The science

Since the claimants in King v Bristow Helicopters failed to prove their cases, a huge amount of research has been undertaken into the interplay between brain injury and conditions such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

Most recently, a study published last month in the American journal Neurology has shown an association between repeated brain injury and depression and dementia in later life, suggesting that at least some depression may be caused by physical injury to the brain.

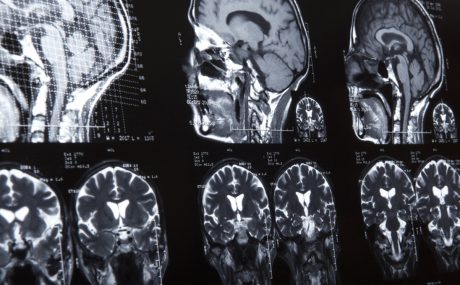

Other depressive episodes may be caused by stress, which releases hormones linked to the shrinkage of the hippocampus, triggering a cascade of mutually reinforcing symptoms. Some depressed patients have measurable biochemical and hormonal alterations in their brains. Increasingly sophisticated forms of brain imaging, such as positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), permit a much closer look at the working brain than was possible in the past. An fMRI scan, for example, can track changes that take place when a region of the brain responds during various tasks. A PET or SPECT scan can map the brain by measuring the distribution and density of neurotransmitter receptors in certain areas.

Use of this technology has led to a better understanding of which brain regions regulate mood and how other functions, such as memory, may be affected by depression. Areas that play a significant role in depression are the amygdala, the thalamus, and the hippocampus, and research has shown that the hippocampus is significantly smaller in some depressed people. Animal studies suggest that antidepressants stimulate the growth and enhanced branching of nerve cells in the hippocampus, indicating that they work by generating new neurons, strengthening nerve cell connections, and improving the exchange of information between nerve circuits.

All of this suggests that psychological symptoms may well result from physical alteration in the structure of the brain and that a highly stressful event may in itself cause such alterations; and that this could well be measurable by way of scanning.

Conclusion

It is time for the law in this area to catch up with the science. The developments anticipated by the majority in the House of Lords in King v Bristow Helicopters have been made, and Scott and Sarah believe that the issue of what constitutes ‘bodily injury’ should now be revisited.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our International Injury pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.