In a case decided recently in the Family Court of England and Wales, the judge considered a wife’s claim to share in her husband’s carry and co-investment in two private equity funds as part of financial remedies following divorce. Lucy Swinton and Ellie Hampson-Jones consider the decision.

The parties involved in A v M [2021] EWFC 89 married in 1994. Divorce proceedings commenced in 2019. This was, therefore, a long marriage with five children borne to the parties.

The wife (“W”) and applicant in the proceedings had “extremely rich parents” and was the beneficiary of valuable trust funds. The husband (“H”) worked in private equity and set up two funds with a business partner between 2015 and 2020. Both of these factors influenced the final outcome of the case.

Background

As set out above, H ran his own private equity fund. Traditionally, investors commit monies to a fund. Once the investment is received, the fund will seek out businesses in which to acquire a controlling interest, with the idea that their involvement will add value to the business. At an opportune moment in the cycle of the market and the lifespan of the business, the business will be sold and the investment in it realised at (hopefully) a profit. Sometimes, given the nature of the beast, there are great successes, as well as occasional disasters. This summary is derived from Coleridge J’s case of B v B [2013] EWHC 1232.

The focus of this article is the approach adopted by Mr Justice Mostyn to the evaluation and sharing of carried interest. ‘Carried interest’ is the fee which partners will receive from a fund provided that certain performance thresholds are met, over and above investors’ original investment. Many consider this to be a type of ‘bonus’ given its connection to performance. Others regard it as a kind of return on investment on the basis that those involved have also often made capital contributions to the fund. In any event, such carried interest is not realised until the businesses in which the fund has invested have had a realisation or exit event. This can take several years.

When dealing with the treatment of carried interest, the family court must grapple with the other spouse’s entitlement. As indicated, carried interest is usually received several years after the establishment of a fund. This can raise complexities if a fund is established during the course of a marriage but fees are received some five to ten years later, long after the marriage has ended.

This is an important case for any families whose financial make up involves private equity/hedge funds or arguably any other deferred return on an asset.

Carried interest

The fair distribution of the ‘carried interest’ produced by H’s funds was a central feature of this litigation.

In A v M, Mr Justice Mostyn set forth that carried interest is neither exclusively an earned bonus (as argued by H) nor a return on capital investment (as put forward by W), but is instead a hybrid of the two with characteristics of both.

Background to the funds

Fund 1 was established by H in 2016. Investors had committed £187 million. The term of the fund was eight years from the date of its close in March 2017, with the possibility of two one-year extensions.

Fund 2 was established in 2018, with its final close taking place in December 2020. Investors had committed £332 million, of which £151 million had been invested. The fund’s term was ten years from the date of closure. However, the term of the fund could be extended or even reduced. It is clear, however, that the point of closure would come after the marriage had ended. Many would argue, therefore, that these ‘returns/fees’ were post-marital and so should not be subject to equal sharing because it is not part of the “fruits of the marital” partnership.

Mr Justice Mostyn was however clear that marital acquest should be calculated as at the date of the final hearing, unless there has been a “needless” delay in bringing the case to trial. This is to reflect that “the economic features of the parties’ marital partnership will have remained alive and entangled up to that point.” Mr Justice Mostyn accepted that he might adopt a different view if a completely new asset were introduced between the date of separation and trial but he did not regard H’s carried interest to be of this nature, given the funds were established during the marriage.

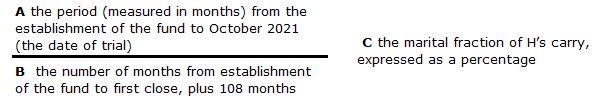

Mr Justice Mostyn stated that his judgment “has at its heart a broad evaluation of fairness”. Accordingly, fairness required that the “marital” portion of the carried interest should be shared equally between the parties. That marital portion should be calculated linearly over time and he set out that the calculation should be A ÷ B = C where:

‘C’ then needs to be multiplied by the projected value of H’s carry to give the value of the “marital” carry which should, on the facts of this case, be shared equally.

Adopting this approach, Mr Justice Mostyn concluded that 53% of H’s carry in Fund 1, and 31% of H’s carry in Fund 2, fairly represented the marital element of each of them.

Mr Justice Mostyn emphatically rejected W’s “untenable” argument that the marital portion should extend beyond the date of the trial to reflect the contribution she continues to make to the family by raising the parties’ 12-year-old daughter. Mr Justice Mostyn, reflecting existing precedent, commented that it is “unprincipled” to argue that earnings which have been generated after the end of an economic partnership should be shared. He went as far as to observe that this argument should “finally bite the dust”.

Where the structure of assets are complex and not immediately available for division, there can be arguments on both sides as to whether the parties should receive their award in the exact same format or whether a better outcome is for one party to be able to extract themselves from certain asset structures such as ongoing businesses/investment funds to enable proper separation. In this case, H argued that any ongoing involvement on behalf of W should be limited in size and range. Reflecting this, Mr Justice Mostyn allocated W’s sharing entitlement exclusively to Fund 1.

In conducting this exercise, rather than simply adding the marital months of Fund 2 to Fund 1 (and awarding 50% of that percentage to W), Mr Justice Mostyn calculated the difference between the projected yields of each fund and concluded that 97.06% of Fund 1 was marital. W was therefore awarded 48.53% of H’s carry in Fund 1 and nothing in relation to H’s carry in Fund 2.

The judgment concluded that it would be “unreasonable” for W to seek the transfer of H’s interest in the funds to her; she would instead receive her share in the carried interest by means of contingent lump sum orders against H. Based on Mr Justice Mostyn’s forecast, W would receive approximately £6.4m in 4 years’ time. From this, W could generate an annual income of approximately £325,000 per annum.

Mr Justice Mostyn acknowledged that, as the crystallisation of carried interest is a future event, there is no guarantee that W’s share of H’s carry in Fund 1 will yield the sums projected. He was, however, satisfied that on the balance of probabilities, W would receive sums of that order. W’s claims for ongoing periodical payments were dismissed. W’s likely future benefit from her parents’ wealth undoubtedly helped to shape Mr Justice Mostyn’s conclusions.

Conclusions

Partner Matthew Humphries comments:

“Mr Justice Mostyn’s analysis in A v M provides a clear method by which to calculate the marital portion of carried interest. This judgment should also now extinguish any arguments to share in future earnings on the basis of ongoing contributions. Taken together, these principles provide comprehensive guidance to practitioners navigating carried interest cases and arguably any cases involving assets that provide a deferred return.”

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Divorce and Family pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.