Music star Prince, who was widely regarded as one of the greatest entertainers, musicians and record producers of his generation, died aged 57 in 2016 after a long career topping music charts worldwide. He left a valuable and complicated estate behind but had not made a will, leading to a six-year legal battle between his family. This article examines the problems that can arise if you die intestate and the risk that your assets will not be distributed in the way you wished.

Prince was twice divorced, had no children, and his parents had died before him, so his estate passed automatically to his six surviving siblings. According to his only full sibling Tyka Nelson, he was outlived by herself, John Nelson, Norrine Nelson, Sharon Nelson, Alfred Jackson, and Omar Baker.

His estate was eventually distributed among three siblings and publishing company Primary Wave, who purchased rights to Prince’s catalogue from three heirs, two of whom have passed away. After a long dispute regarding the estate’s value, it was recently revalued at £114m, nearly twice an earlier assessment. It is hoped this ends the six-year legal battle to have the estate valued and distributed.

Regardless of the size of your estate, how can you avoid leaving similar problems to those caused by Prince dying without a will?

If you die in the UK without a will, you are considered to have died ‘intestate’, which means your estate is distributed according to set rules depending on people’s relation to you. This can lead to problems and, unfortunately, litigation, as the intricacies of family life do not always fit in neatly with the intestacy rules.

Intestacy rules in England and Wales

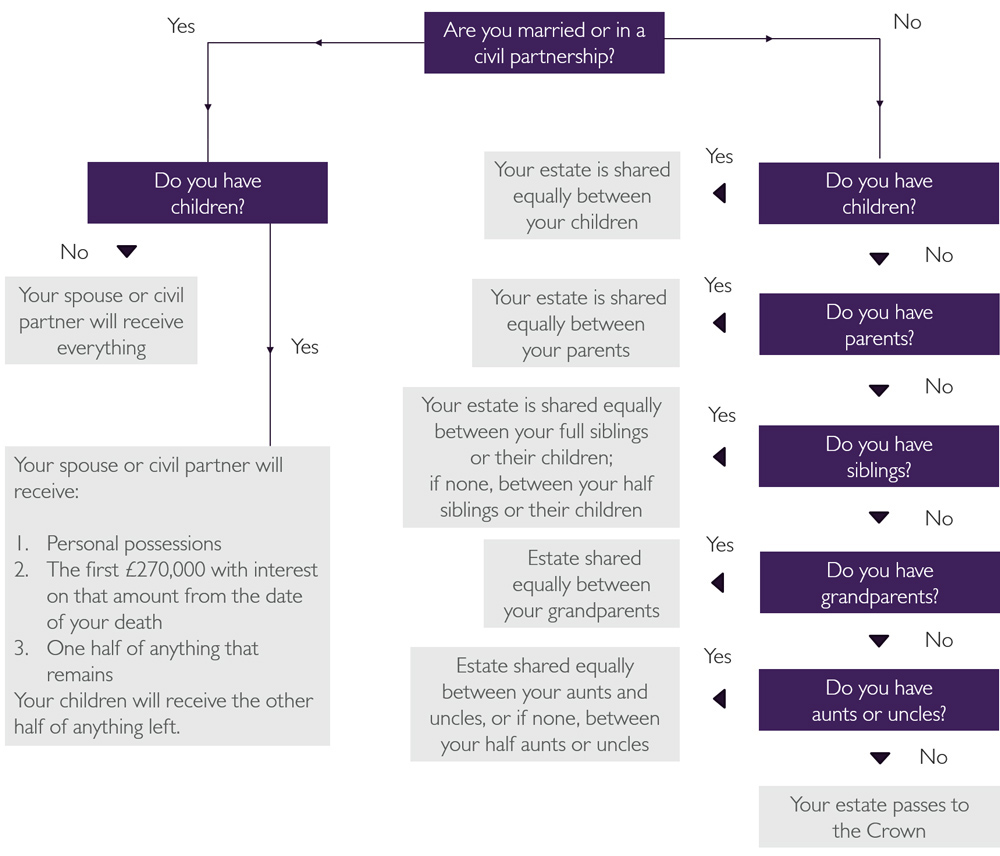

The current rules in England and Wales were introduced in October 2014 and are contained principally in parts 3 and 4 of the Administration of Estates Act 1925. These provisions set out that the division of an intestate estate will follow a fixed order based on the following relationships (click on the flowchart to see a larger version):

Key points to remember in relation to the intestacy rules include:

- The term “children” includes adopted children but not stepchildren

- Children will only receive their inheritance if they reach the age of 18 or are married or enter a civil partnership before they become 18

- If relatives are not living at the date of death but their children are, they would usually inherit the share their parent would have taken if they were still alive.

Risks of dying without a will

The rules do not account for the multitude of modern family dynamics, including second marriages, divorces, stepchildren, estranged family members, separated partners, unmarried or cohabitating couples. The rules are still largely based on the societal norms in place when the rules were created: 1925.

By failing to make a will, those outside your direct family will not inherit any of your estate regardless of your intentions.

Possibility of litigation

Although the intestacy rules dictate how your estate should be distributed, certain people linked with the person who has died (including financial dependants or people living with the deceased) can still make a claim for financial provision under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975.

This came up last year in two example cases. In Higgs v Morgan, the entire estate of a stepfather passed to seven distant cousins and not to his stepson. In Simsey v Salandron, a father had gifted a property to his son in a 2017 will, but his new marriage in 2019 had revoked that will. In both cases, the individuals’ estates had been distributed according to intestacy rules, but both were successfully challenged under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975.

Alternatively, beneficiaries can apply for a deed of variation or a deed of family arrangement within two years of the death. This is an agreement between all the people who would have inherited under the rules to distribute the assets differently, including to people who would not have inherited under the intestacy rules or changing the proportions of distributions.

Both are complex and costly situations, the risks of which can be reduced by leaving a valid will.

Conclusion

Distributing an estate under the intestacy rules can be time-consuming and costly. According to the heirs of Prince’s estate, during the first three years following his death, they had racked up administrators’ fees of $45m, including $10m in legal fees.

Research carried out in October 2021 by pollster Opinium found that a significant proportion of the 1,043 UK retired and semi-retired adults aged 55 and above surveyed had not made a will.

The research found:

- More than one in 10 over 75s (12%, equating to nearly 700,000 people) have not made a will

- Some 22% of 65 to 74-year-olds (equating to 1.5m people) have not made a will

- Only 30% of people aged 75 and above have put a power of attorney (“POA”) arrangement in place, meaning four million Britons do not have a POA

- More than five million people aged 65 to 74 do not have a POA in place.

Additional research (not based on age restrictions), carried out in June 2020 of more than 1,000 members of the public showed that just 29% said they have an up-to-date will that reflects their current intentions.

It may seem laborious and forever at the bottom of your to do list, but having an up to date will ensures that you make decisions for yourself and gives you peace of mind.

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Trust and Probate Litigation page.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.