English practitioners have long had a sense of the UK as being a preeminent jurisdiction for fraud claims. Recent data analysis by Stewarts and Solomonic has now supported this.

As part of our 2025 report into commercial fraud claims, Charlie Mercer reviewed which nationalities are represented as parties in fraud claims in the English courts. He also spoke to experts from some of the most well represented jurisdictions for their view on why England and Wales is an attractive system for bringing litigation.

International parties in English fraud claims

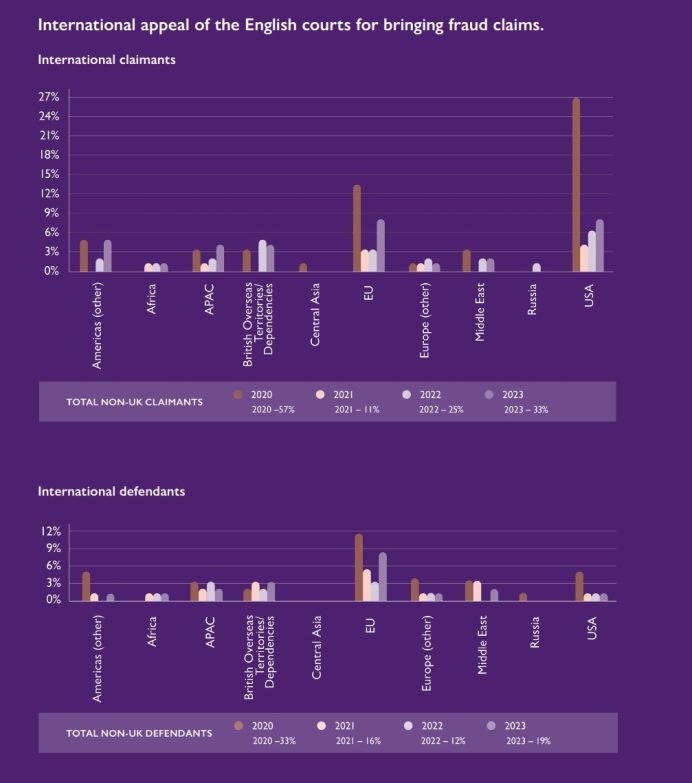

Since 2020 (the starting point for our data source), a third of claimants and a fifth of defendants have been resident overseas. As to those:

- For claimants, the EU and the USA are consistently the most represented geographies. Other consistently represented regions include Asia-Pacific (APAC), the Middle East, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, and the Americas.

- For defendants, the EU is again consistently the most commonly represented region, with the Middle East, APAC, British Overseas Territories/Dependencies and USA featuring as other key regions.

The data needs to be treated with caution. For example, looking at parties’ residence misses English subsidiaries of non-English multinationals. Based on the claim forms currently available for 2024, there is also insufficient data available to draw meaningful conclusions (which is why 2024 is not included here).

There are also other ways to assess how international a case is. For example, the Commercial Court records that 75% of cases issued from October 2023 to September 2024 were international. It defines “international” as “not domestic”, and in that context defines domestic as where (i) the subject matter of the dispute between the parties is related to property or events situated within the United Kingdom, and (ii) the parties are based in the United Kingdom relative to the dispute (in other words, that the part of the business relevant to the dispute is carried on in the UK, regardless of whether the business is incorporated, resident or registered overseas).

What can we take from this? At one level, it is clear that parties from all over the globe are litigating fraud claims in the UK. We can guess the perceived benefits. English practitioners have long had a sense of the UK as being a preeminent jurisdiction for fraud claims and offering a number of benefits, be that the availability of worldwide freezing and search orders, the broad disclosure regime or the ability of the courts to handle complex claims. All of this was reflected in the comment of Mr Justice Knowles in last year’s judgment in Mozambique v Privinvest, which encapsulated that self-image:

“The parties to these proceedings came from many parts of the world. The trial was followed from many parts of the world. It was a privilege to see shared confidence in a fair trial here, in England and Wales. A lot of resources were consumed. But not unduly so: a fair trial is important to the rule of law, on which every country in the world ultimately depends and from which every country in the world ultimately benefits.”

With that in mind, we spoke to friends and colleagues in some of the most prevalent geographies to get their views on the appeal of the English courts for litigating these types of claims.

Germany

Wolfgang Sturm and Jonas Kiehl, Broich

Fraud claims are an increasing feature of the German courts, driven by mass litigation such as “Dieselgate” and other high-profile claims, including the litigation arising from the collapse of Wirecard. As regards investment fraud, the German legislator recently improved the Capital Markets Model Case Act (Kapitalanleger-Musterverfahrensgesetz – KapMuG) with the aim to speed up proceedings. Apart from that, practical hurdles for (quasi) collective redress remain rather high in Germany.

The high number of EU parties in England is presumably due to strong commercial ties. However, London generally has a good reputation in Germany for pursuing fraud claims, both through the courts and as an arbitral seat. It is seen as efficient, neutral and apolitical. The wide disclosure regime also distinguishes it from what is available in Germany, where it is difficult to obtain documents beyond what is in the controlling sphere of the respective parties. There is also a greater certainty about what a court is likely to find, given the emphasis on prior case law.

A recent downside has been the lack of clarity after Brexit about how English judgments can be enforced abroad. The approach to contractual interpretation can also be more restricted in England. In Germany, a court might find that a contract means the opposite of what is written based on the parties’ intention, which would not happen in England. The distinction between solicitors and barristers is also an unfamiliar element of the English system.

USA

Gonzalo Zeballos and Oren J. Warshavsky, BakerHostetler

The prevalence of US parties in England is most likely down to a few factors. Most obviously, there is the shared language. There are also clearly strong commercial ties between the US and the UK, which brings those parties into contact and which is only likely to increase following the recent trade deal. The English system also has a reputation for working well and being recognisable to US practitioners, such as being based on the common law.

That being said, it can be surprising to US practitioners just how different the US and English systems are. There is a difference in style, such the manner in which oral argument is conducted, and the rules in the way the evidence is considered and presented can be quite a difference. The absence of depositions in English civil practice is often a surprising and unwelcome revelation to US lawyers. The bifurcation between solicitors and barristers is also unfamiliar.

Another significant difference is on costs. There are two aspects to that. First, there is no fee shifting; in the US, the loser pays in only very limited circumstances. Second, because there is no fee-shifting, there is no security for costs in the US. This makes the US a friendlier jurisdiction at the front end for fraud victims, particularly where claims are of a lower value. However, the high-cost of litigation with no ability to recoup those costs arguably poses access to justice issues for some fraud victims, though contingency fees and alternative fee arrangements (including litigation funders) can mitigate those issues.

India

Sherina Petit, Head of International Arbitration and India practice, Stewarts

There have been a number of recent, high-profile fraud claims in the English courts with an Indian connection. These include a claim against the Indian financial group IIFL Wealth relating to the collapse of Wirecard, claims against Pramod Mittal brought by the liquidators of Global Steel Holdings Limited and claims in fraudulent misrepresentation and unlawful means conspiracy for InterGlobe Aviation, for whom Stewarts is currently acting.

The presence of India-related disputes can be put down to a number of factors, including commercial and cultural ties. International contracts in India are also often governed by English law.

The involvement of Indian parties before the English courts is only likely to increase in the coming years. India has emerged as one of the largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) for the UK in recent years, and this is likely to be turbocharged by the UK-India trade deal agreed earlier this year and the 2030 Roadmap for India-UK future relations.

However, the UK has competition, most notably from Singapore. Indian parties are now the third largest foreign users of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre, albeit these claims are often of low value. Nevertheless, the UK needs to be conscious that its position is contested.

Singapore

Danny Ong, Managing Partner and Director, Setia Law

Jurisdiction tends to be determined by a combination of where structures are located, the subject matter of the claim, the prominence of the jurisdiction as a financial centre and the attraction of the jurisdiction for holding assets. In that sense, the traffic of disputes between London and Singapore is likely to be primarily driven by the last two of these factors, as well as historical ties and the familiarity of the common law system.

Fraud is a very significant feature of litigation in Singapore. Although historically the value has been lower than might be expected in the UK, that has begun to change, and it is now common to see very high-value disputes. Cases are always complex and are often multi-jurisdictional. There has been an uptick in disputes relating to cryptocurrencies and fraudulent investment schemes. Singapore’s growth as a centre for private wealth may also become a feature of such claims in future years.

In that context, the availability of interim measures in the UK is attractive, and there is a familiarity with running parallel proceedings between Singapore and the UK or other common law jurisdictions.

The Cayman Islands

Nick Hoffman, Harneys

Cayman has a thriving legal system that is sophisticated at dealing with fraud disputes. The courts handle disputes of a value and complexity to match the London courts. This is partly driven by Cayman’s position as the largest funds jurisdiction and the fact that the Topcos in complex group structures are often incorporated here. For example, the Cayman courts are currently handling some of the biggest restructuring cases in the world, including that of Evergrande.

Judges have historically had a clear intention to keep claims involving Cayman Island companies within the Cayman courts, subject to the usual principles. A Cayman (or indeed a British Virgin Islands or Bermudan) company would usually only be drawn into London litigation because of some function it played as part of a wider financial structure.

With all that said, the view of the London courts remains high for all the reasons one might expect, including because of the quality of the judges, the overlap in practitioners and the predictability of enforcing judgments.

Although, as expected, the English system is comfortingly familiar, in part due to the historical connections, there is divergence. For example, Cayman has not adopted a similar set of reforms to the Woolf Reforms, which brought in the Civil Procedure Rules in England. Also, the Financial Services Division (the equivalent of the London Commercial Court) has its own set of rules, and there are areas where the case law has departed significantly from England, such as in relation to the winding up of companies. These are often not enormous departures, but they are different and intended to be different given the financial services focus of the Cayman economy and the Cayman courts. However, there is more familiarity than with other jurisdictions.

Middle East

Keith Hutchison, Clyde & Co

London is seen as a top-tier jurisdiction for litigating fraud disputes. This will partly be driving the numbers of UAE litigants in the UK, as well as the strong bilateral, historical and cultural ties between the two jurisdictions.

However, the courts of the UAE, and particularly the common law courts in the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM), have developed significantly in recent years and offer real competition to London. There has been a significant increase in the certainty of outcomes, as well as an increased predictability in the enforcement of UAE judgments in the UK and vice versa. The quality of the judiciary is also good, the common law system used in the DIFC and ADGM courts is attractive, and they are able to deal with complex and high-value cases, also in the English language. Notably for fraud claims, it is also now straight-forward to obtain worldwide freezing orders in the DIFC and ADGM courts (which are available also where the main proceedings, whether extant or intended, are in another jurisdiction).

The types of disputes seen in the UAE are partly driven by underlying economic developments. Traditionally, fraud claims have centred on common industries or sectors such as financial investments, commodities and trading. More recently, regulatory bodies in the UAE (including in the DIFC and ADGM) have introduced sophisticated regulation regarding crypto assets, which has led to a groundswell of investment in that asset class and which, in turn, has led to litigation, including the landmark decision in (1) Gate Mena DMCC (2) Huobi Mena FZE v (1) Tabarak Investment Capital Limited (2) Christian Thurner [2020] DIFC TCD 001. There have also been a number of high-profile fraud cases that have driven litigation, including the collapse of NMC Healthcare.

Stay ahead of the evolving landscape of fraud litigation with our latest report.