Amy Heath and Katherine Fitter write for PI Focus, reporting on a recent medical negligence ruling in the following article titled ‘Clinical Approach’. This article is a summary of the Court of Appeal clinical negligence case of Lesforis v Tolias [2018] EWHC 1225 (QB), in which judgment was handed down on 25 March this year.

Background

The claimant, Mrs Lesforis, was 56 at the time of the events giving rise to her claim in June 2013.

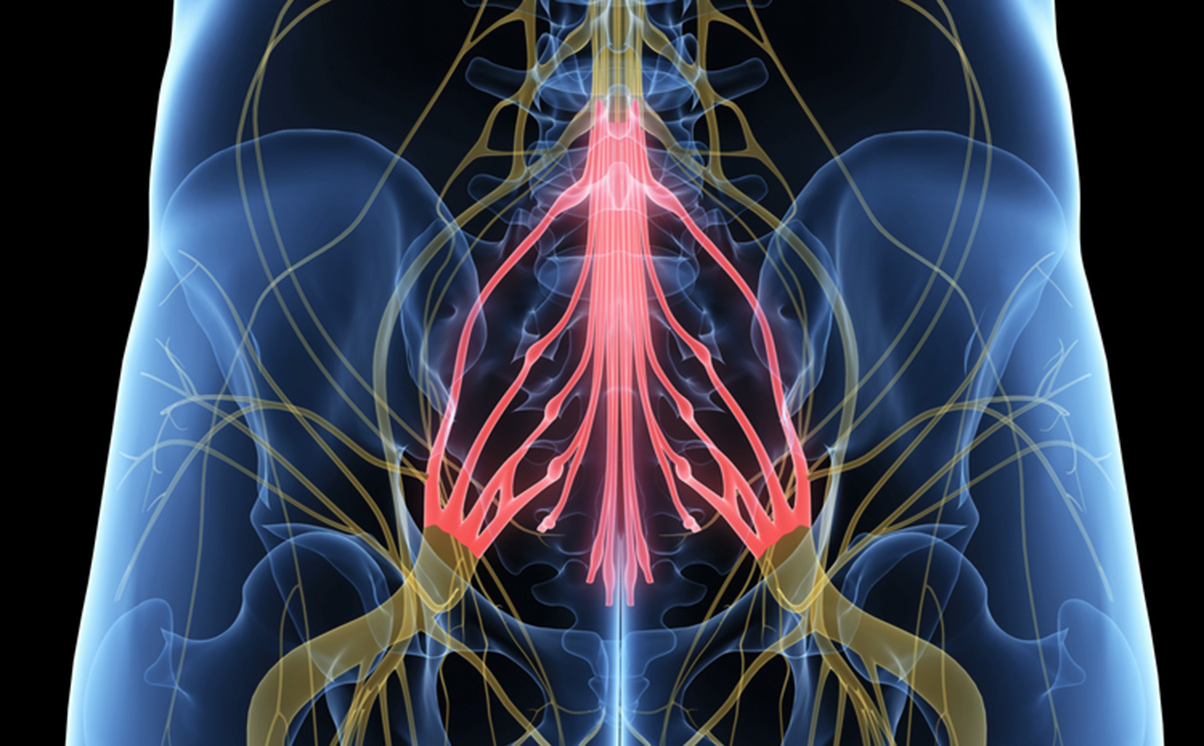

In 2007, the claimant began to suffer from lower back pain. MRI scanning confirmed the presence of moderate to severe canal stenosis at the L3/4 level. Between 2007 and 2012, treatments had proved unsuccessful in resolving her pain. As a result, surgery in the form of a lumbar decompression and posterolateral fusion was recommended.

Due to NHS delays, the claimant elected to use her private health insurance to expedite surgery. She was admitted to the Harley Street Clinic for surgery under the care of the defendant on 27 June 2013.

The operation itself was uncomplicated. Following the surgery, the claimant was to remain immobilised for 48 hours due to a small dural tear that had occurred and been swiftly repaired during the surgery.

The claimant was to be given low molecular weight heparin (Clexane) as chemoprophylaxis to reduce the risk of venothromboembolism (VTE), which can cause deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This was given around three hours after surgery.

On 29 July 2013, the claimant was unable to wiggle her toes and move her ankles. No out of hours or weekend MRI scanning was available at the clinic, and so a CT scan was carried out. This showed no obvious haematoma.

Steroids were commenced and then a decision was taken to re-operate. A solidified clot was found to be compressing the spinal cord and this was removed.

Post-operatively, the claimant was still unable to move her toes and ankles.

The claimant subsequently underwent rehabilitation. She is now largely wheelchair reliant with no sensation from L1-L4 and altered bladder and bowel function.

First instance decision

There were three allegations against the defendant, all of which were denied:

- Chemoprophylaxis for DVT was given too soon following surgery in view of the risk of postoperative haematoma.

- An MRI scan should have been carried out following the onset of neurological deficit.

- The second operation should have been carried out eight hours earlier.

In respect of the first allegation, the defendant submitted that there was nothing in the NICE Guidance in place at the time that related to timing of chemoprophylaxis. There was, therefore, a wide range of practice and the timing in this case was not negligent according to the Bolam test.

In response to the second and third allegations, the defendant submitted that he had all the radiological evidence he needed from the CT scan. The decision to delay surgery while giving steroids an opportunity to work was acceptable. It was a difficult clinical situation where the neurological deficit did not correspond with the level at which surgery had been carried out.

Mr Justice Spencer found that there was no negligence in respect of the second and third allegations.

While an MRI scan would have given a fuller clinical picture and it was, he noted, surprising that complex spinal surgery was carried out where there is no emergency MRI scanning on site, it would not have changed the course of events, as the defendant performed the same surgery on the basis of the CT scan. The clinical picture was a difficult one on the afternoon and evening of 29 June 2013, and there was no undue delay.

Timing of chemoprophylaxis

In his witness statement, the defendant gave evidence that giving early chemoprophylaxis was his practice for all patients.

He said: ‘An overweight patient such as Mrs Lesforis, particularly one who is going to remain flat for 48 hours after the operation because of the durotomy, is at risk of venous thromboembolic event and therefore Clexane is indicated, along with intermittent calf compresses which were also prescribed. However, it is my normal practice to give anti DVT chemoprophylaxis very early postoperatively to all my cranial or spinal patients and I am surprised to see it is criticised in the Letter of Claim.’

Expert evidence

In the joint expert meeting, the defendant’s neurosurgical expert, Mr Cadoux-Hudson, stated that there was a lack of quality clinical evidence in this area and there are a range of different practices as to the timing of chemoprophylaxis. His view was that the precise timing is at the surgeon’s discretion having weighed up the risks and benefits.

Mr Leach, the claimant’s neurosurgical expert, agreed that it is a balanced judgement between the risk of bleeding and the risk of VTE. However, in his view, no reasonable body would give chemoprophylaxis within six hours due to the increased risk of bleeding and potential haematoma formation.

During cross examination, Mr Leach stated that he was not aware of any surgeons giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours.

He said if he was presented with evidence that there was a reasonable body doing so, or a protocol advocating this at a neurosurgical centre, he would accept that as reasonable. Mr Leach acknowledged the lack of good clinical evidence available, and faced with that he felt that he was only able to refer to relevant guidelines and his own experience.

In cross examination, Mr Cadoux-Hudson again noted the lack of quality clinical evidence in this area.

He further noted that there is no specific data to say that giving chemoprophylaxis at three hours presents a higher risk than in any other period.

In re-examination, Mr Cadoux-Hudson for the first time expressed the view that giving chemoprophylaxis at three hours in this patient would fall within the accepted variation of practice.

Decision

Mr Justice Spencer preferred Mr Leach’s evidence. He was impressed that Mr Leach had indicated that he was willing to change his opinion if presented with evidence that there was a reasonable body advocating chemoprophylaxis within six hours.

However, the defendant had failed to present such evidence and Mr Leach was, therefore, unaware of such a body. In the judge’s view, this was likely because there was not one.

The judge found that the three risk factors for VTE identified in the claimant’s case did not go to the timing of chemoprophylaxis, but to the giving of chemoprophylaxis.

There was also no suggestion in the defendant’s evidence that he had carried out an assessment of the specific risks and benefits of chemoprophylaxis for the claimant. Rather, he specially stated that giving early chemoprophylaxis was his routine practice.

This led the judge to find that the defendant’s ‘use of [low molecular weight heparin] after spinal surgery was cavalier and outside the range of normal practice at the relevant time’.

Causation

On causation, Mr Justice Spencer observed that the starting point was not the absence of evidence in the literature that giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours of spinal surgery increases the risk of a post-operative haematoma.

If it did not carry this risk, giving early chemoprophylaxis would not require the surgeon to carry out a risk benefit analysis and the subsequent 2018 NICE Guidelines would not recommend giving it routinely at 24 hours after surgery rather than earlier.

The judge therefore found that, in this case, giving early chemoprophylaxis at three hours post-surgery caused, or materially contributed towards, the formation of the haematoma. Had it not been given at that time, either the haematoma would not have developed, or it would have been smaller and would not have impinged on the dura.

The appeal

The defendant sought leave to appeal on 11 grounds and was granted permission on just one.

The defendant submitted that although the judge had accepted the three risk factors for VTE that applied to the claimant, he dismissed them as irrelevant to the timing of the administration of chemoprophylaxis.

In doing so, he failed to have sufficient regard to the underlying clinical judgment to be made as to striking a balance between the risks and benefits of giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours of surgery.

He therefore failed to address the underlying question, which was whether the claimant had shown in her case that the risks of giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours of surgery outweighed the benefits of doing so.

It was argued that the focus of both the judgment and the evidence from Mr Leach was on what is accepted as routine practice, and sufficient regard had not been given to what applied to the claimant. Although the defendant did not carry out a specific risk assessment and followed his normal practice, it was argued that this was only a breach of duty if giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours would have been negligent, had such an assessment been carried out.

The Court of Appeal’s decision

The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. The lead judgment was given by Lord Justice Hamblen, with which Lord Justice Patten and Lord Justice Holroyde agreed.

Four reasons were given for dismissing the appeal.

Firstly, the Court of Appeal found that the judge had made findings regarding the relevance of the three risk factors. In cross examination Mr Leach had said that the risk factors did not support giving earlier chemoprophylaxis and that they went to the use of chemoprophylaxis, not timing. It was open, therefore, to the judge to draw the conclusion that the risk factors gave no reason to depart from routine practice.

Secondly, it was observed that even if the risk factors were relevant to timing, Mr Leach was clear that giving chemoprophylaxis within six hours represented a breach of duty. Mr Cadoux-Hudson gave contrary evidence in re-examination, but the judge was entitled to reject this.

Thirdly, the Court of Appeal did not agree that the judge had considered the wrong question. The risk factors identified did not justify departure from routine practice, and therefore it was appropriate for the judge to consider what should be done in routine practice.

Fourthly, it was noted to be a striking feature that the defendant’s evidence was that he routinely gave early chemoprophylaxis. He did not ever suggest that he carried out the risk benefit analysis, which the experts agreed should be carried out.

This article first appeared in PI Focus, May 2019 edition, and can be viewed here (subscription required).

You can find further information regarding our expertise, experience and team on our Clinical Negligence pages.

If you require assistance from our team, please contact us or alternatively request a call back from one of our lawyers by submitting this form.

Subscribe – In order to receive our news straight to your inbox, subscribe here. Our newsletters are sent no more than once a month.